Ecotone

(noun) Where multiple social-ecological communities transition and cohabitate.

8/20/24 - 8/23/24

Puyallup River, Pacific Northwest

Loading...

Scroll slowly to explore →

From August 20-23, 2024 we walked from the mouth of the Puyallup River toward its headwaters on Tahoma/Mt. Rainer*, gathering plants, fungi and minerals to create a dyed map of the river as we experienced it.

*A note on naming - Indigenous people/s of the Salish Sea call this mountain many different names. “Tahoma” is an anglicized pronunciation of Lushootseed, Cowlitz, and Sħáptənəxw names for the mountain.

U.S. settler society honors in name Peter Rainier, a British naval officer and mercenary for the East India Company, who never once saw the mountain or set foot in this area.

In the Puyallup language, this mountain is named “mother of waters”.

We passed through various communities –

Tacoma, Fife, horsetail, Puyallup, early morning fishers, alder, Alderton, blackberry, tansy, seasonal fruit pickers, Bowman Hilton RV Park residents, semi-truck drivers on WA State Route 162, late summer pollinators, Orting, snowberry, more blackberry, rust, butterfly bush, afternoon walkers, mill town residents with gates and no doorbells, red cedar, queen anne’s lace, deer, douglas fir, more blackberry, quarry truckers

– perceiving, fleetingly, the transitions between each of them, the ecotones.

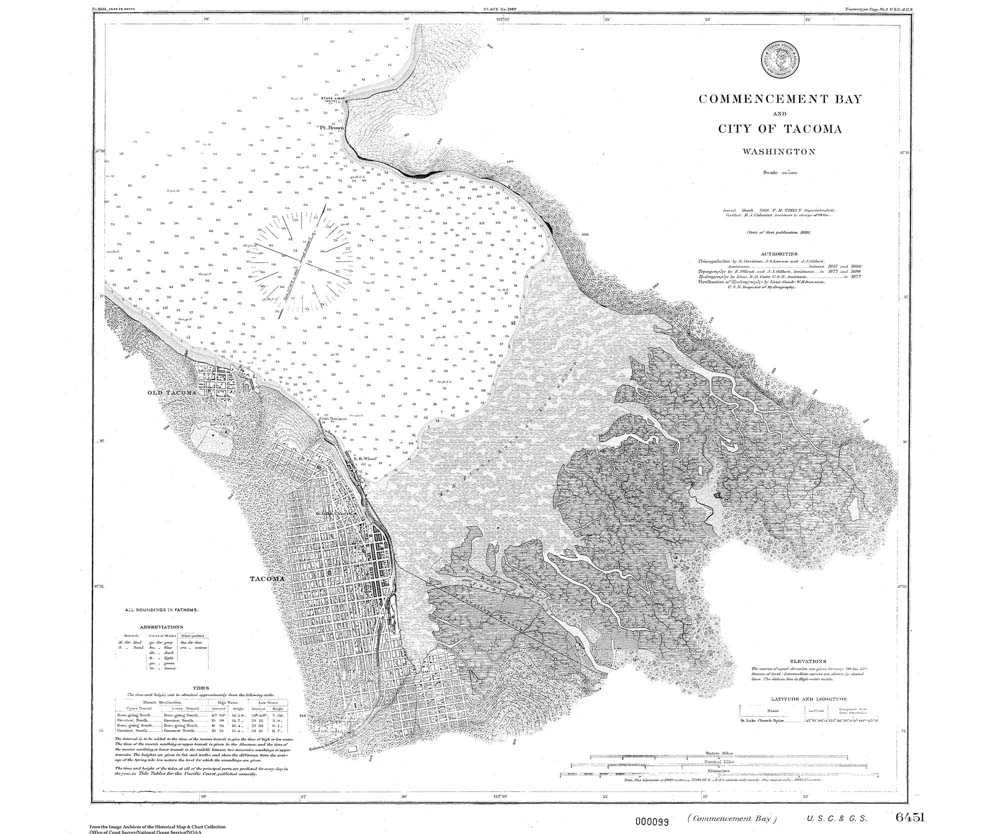

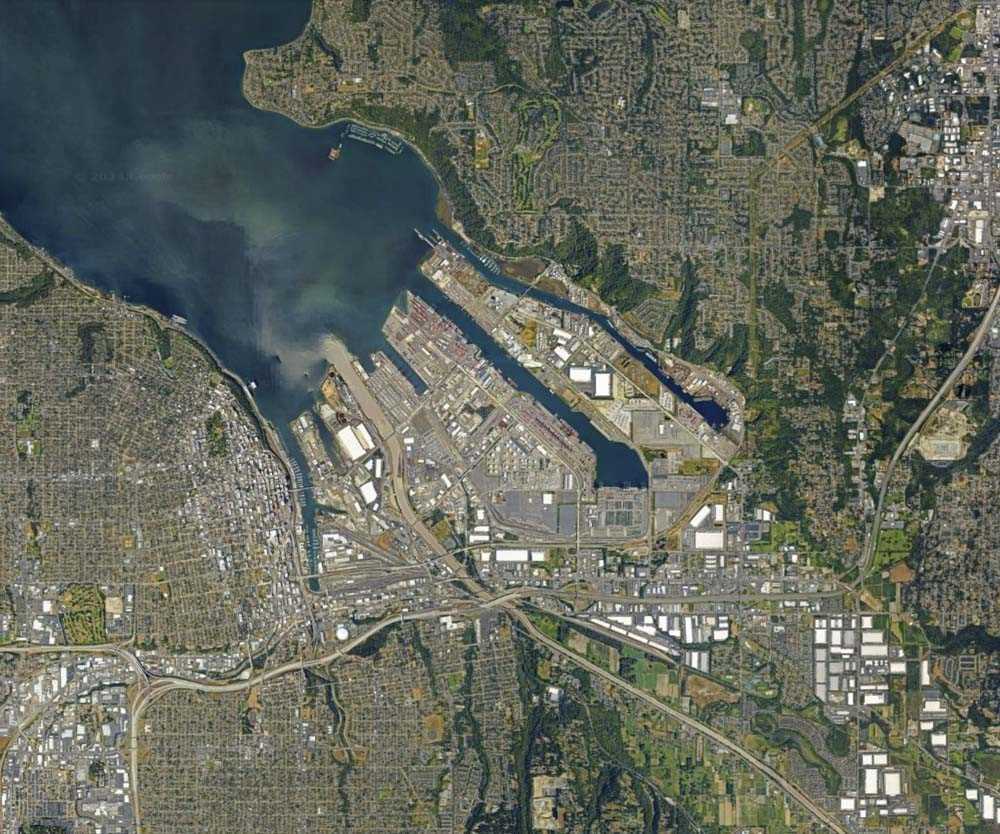

Our journey began at Commencement Bay, the terminal point of the first cross-continental railroad.

Credit University of Washington Archives

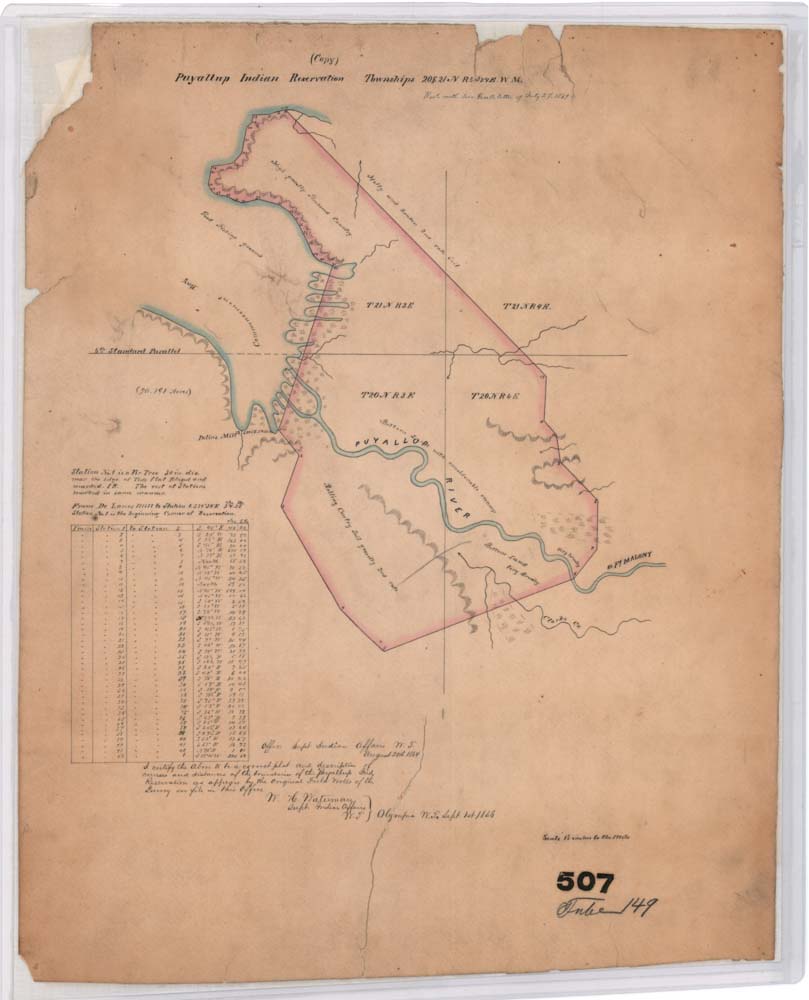

Construction began on the railroad terminus in Tacoma in 1873. An industrial boom and massive dredging of the remaining tidal flats followed the completion of the railroad. This development was only possible because of the prior dispossession of Puyallup, Nisqually, Muckleshoot, and Klickitat people from these lands.

Credit Library of Congress

In the 1850’s, increased settler presence and extractive industry produced raids and massacres. Settlement was facilitated and encouraged by state and federal governments. The Superintendent of Indian Affairs and Washington territorial governor, Isaac Stevens, sought to enshrine settler presence and quell Indigenous resistance by drafting the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek. The treaty established three reservations of greatly varied arability, granted millions of acres of land to the United States, paid signatory tribes 20 years of compensation, and enshrined perpetual fishing and hunting rights.

Credit Library of Congress

On an unseasonably drizzly August day, we walked up to the gate of the shuttered WestRock plant, a paper mill that had been pouring toxic effluents into the Puyallup River for decades.

Today, countless industries and infrastructures–paper mills, oil refineries, shipping terminals, roads, lumber mills and extractive industries–find their homes along the river.

Courtesy Google Earth

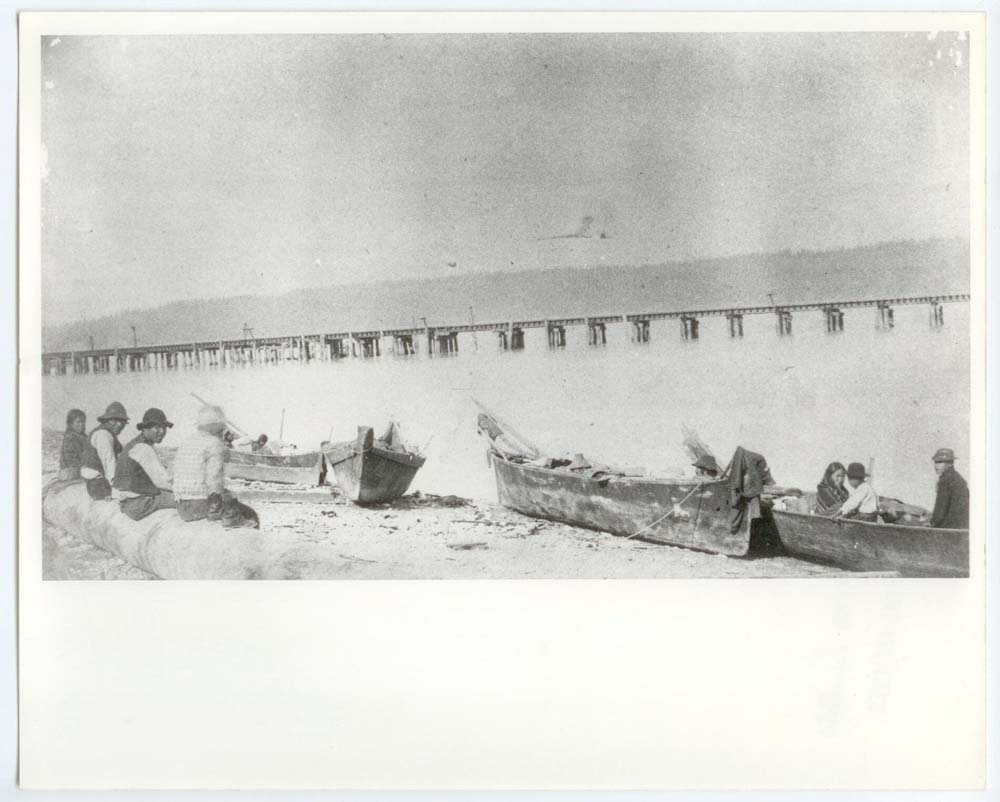

But Puyallup life has always been organized around the river. Village locations, place names, and foodways often center on the river. Puyallup people call themselves in Lushootseed “people from the bend at the bottom of the river”.

Courtesy of Puyallup Tribe Historic Preservation

Plant and animal life centers on the river, too. The salmon which spawn and return to the Puyallup River feed many other animals and fertilize the forests with their bodies.

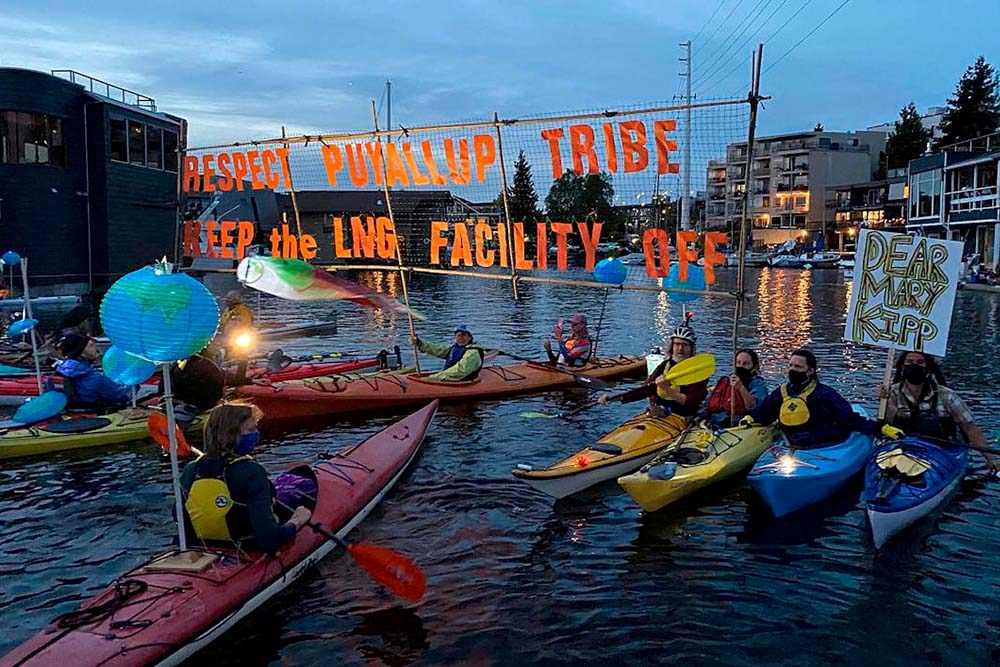

Puyallup people have resisted the profound and ongoing injuries to the river represented by colonial land use. They pushed state and federal agencies to force WestRock to take steps toward protecting salmon. They successfully led a campaign against the operations of an expanded liquified gas terminal on the river. The tribe continues to be the foremost steward of the Puyallup River.

Courtesy of Bellevue Reporter

We were soon told by a security guard that the road we had walked up was private and that we should turn back.

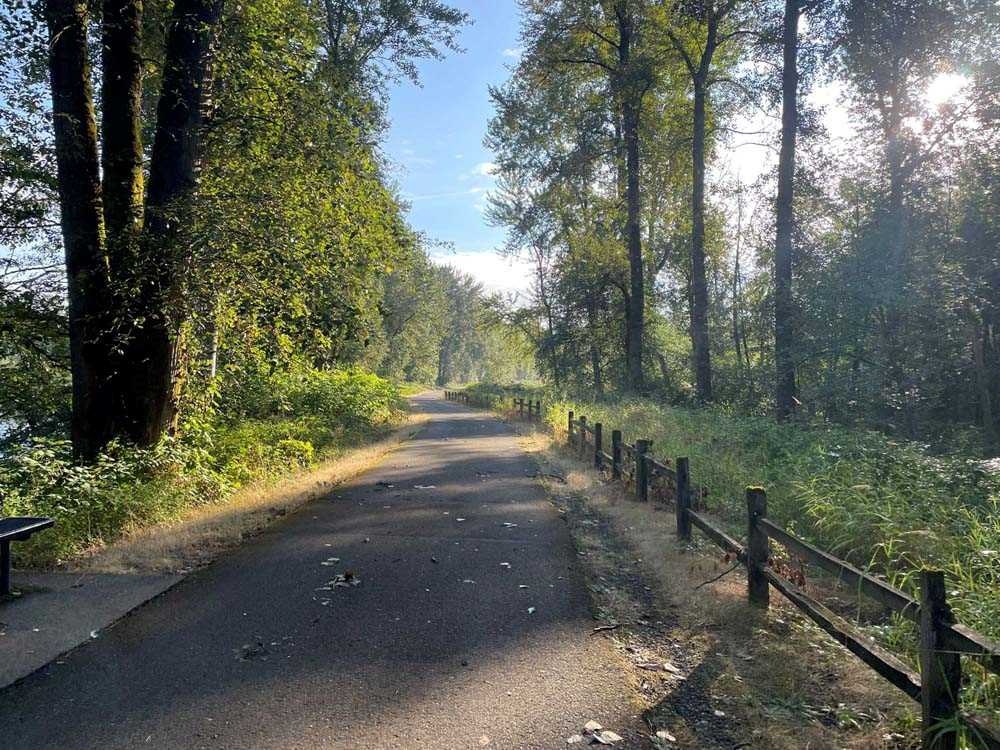

In trying to walk continuously along the river, we came across many obstacles. Some were decidedly physical and human made–embankments too steep to walk on, roads without sidewalks, brambles that had grown over public walking paths. Other obstacles, like “no trespassing” signs were more coercive than physical. The ability to access the river with relative ease, in relative safety is unevenly experienced according to one’s physical capacities and positionality vis-a-vis the settler state and property-protecting police apparati.

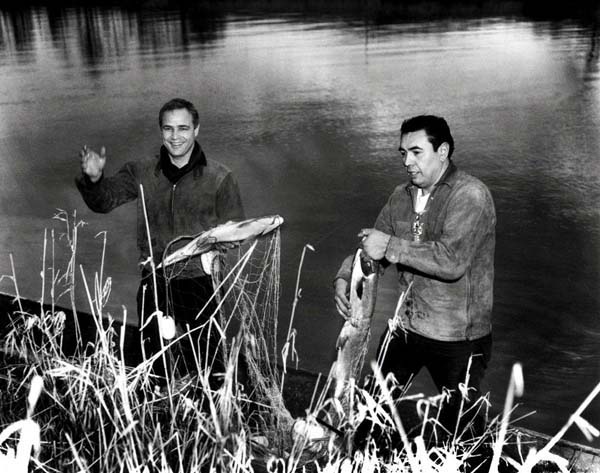

David Leach, courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian

Puyallup fishers used to be robbed, beaten, fined or arrested by the police for exercising treaty fishing rights enshrined in the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek. Amidst the political climate of the Termination Era and declining salmon populations, Washington state increasingly arrested or seized the catches of Puyallup and other Coast Salish fishers. This breach of treaty rights ignited an Indigenous uprising across the northwest known today as the Fish Wars. Through fish-ins and stand-offs along the Puyallup River, Puyallup people won 50% of all salmon harvest in the state of Washington as a result of the ensuing 1974 U.S. v Washington Boldt decision.

Robert Satiacum and Marlon Brando, courtesy of National Museum of the American Indian

Recognizing that we couldn’t start exactly at the river’s mouth, we turned around and headed toward the mountain.

We used a variety of tools and rules to structure our walk, all of which we carried on our backs and in our heads.

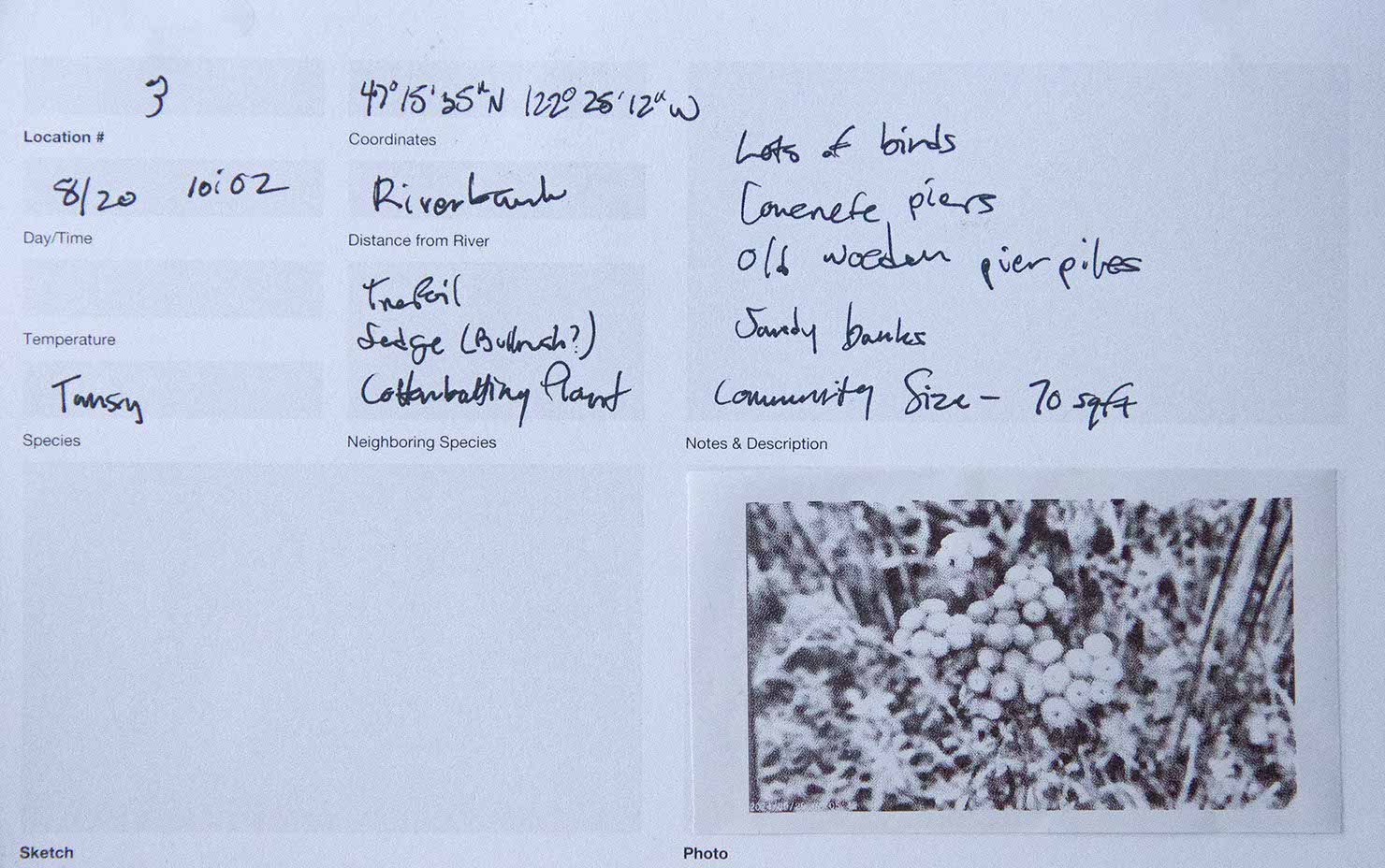

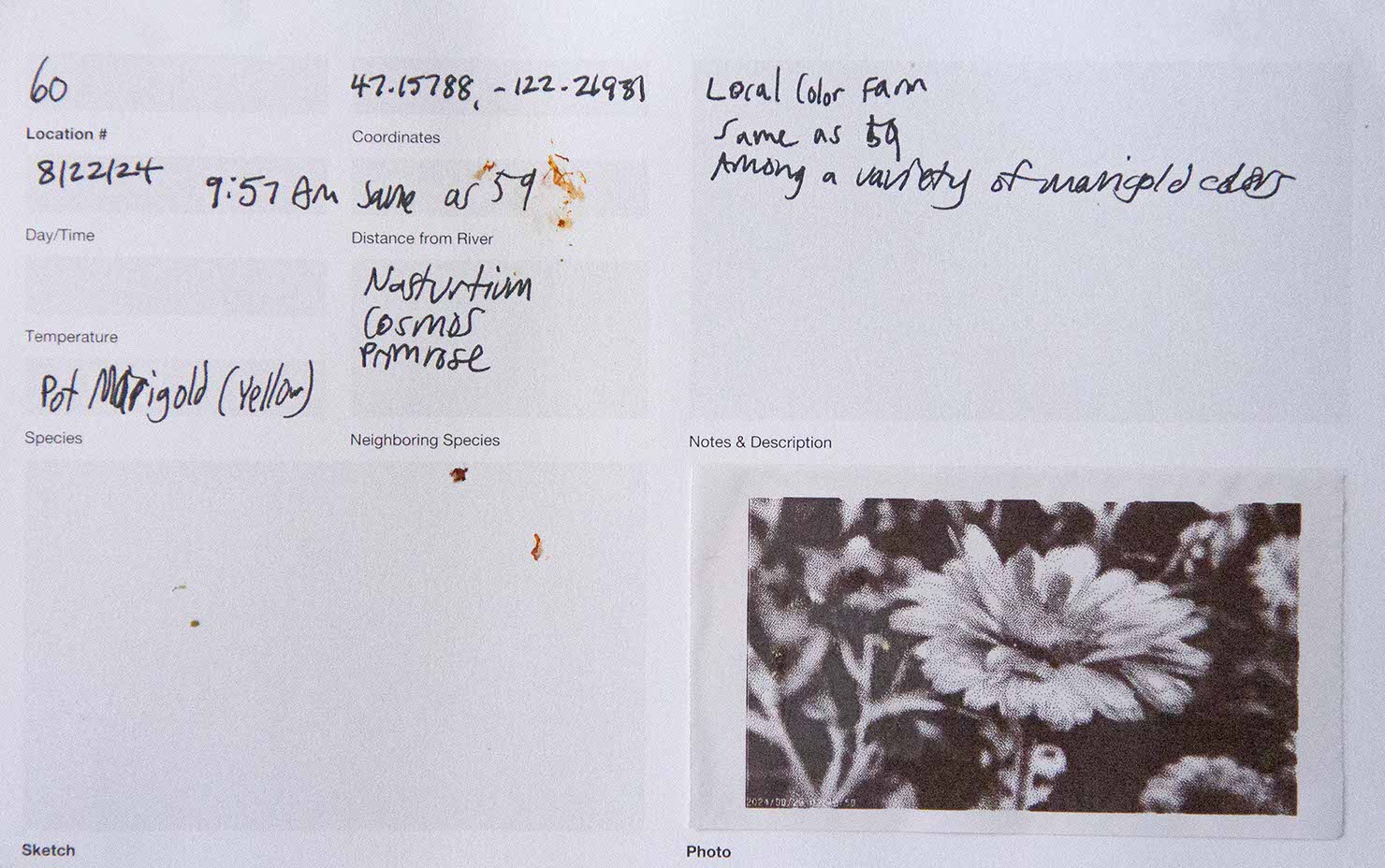

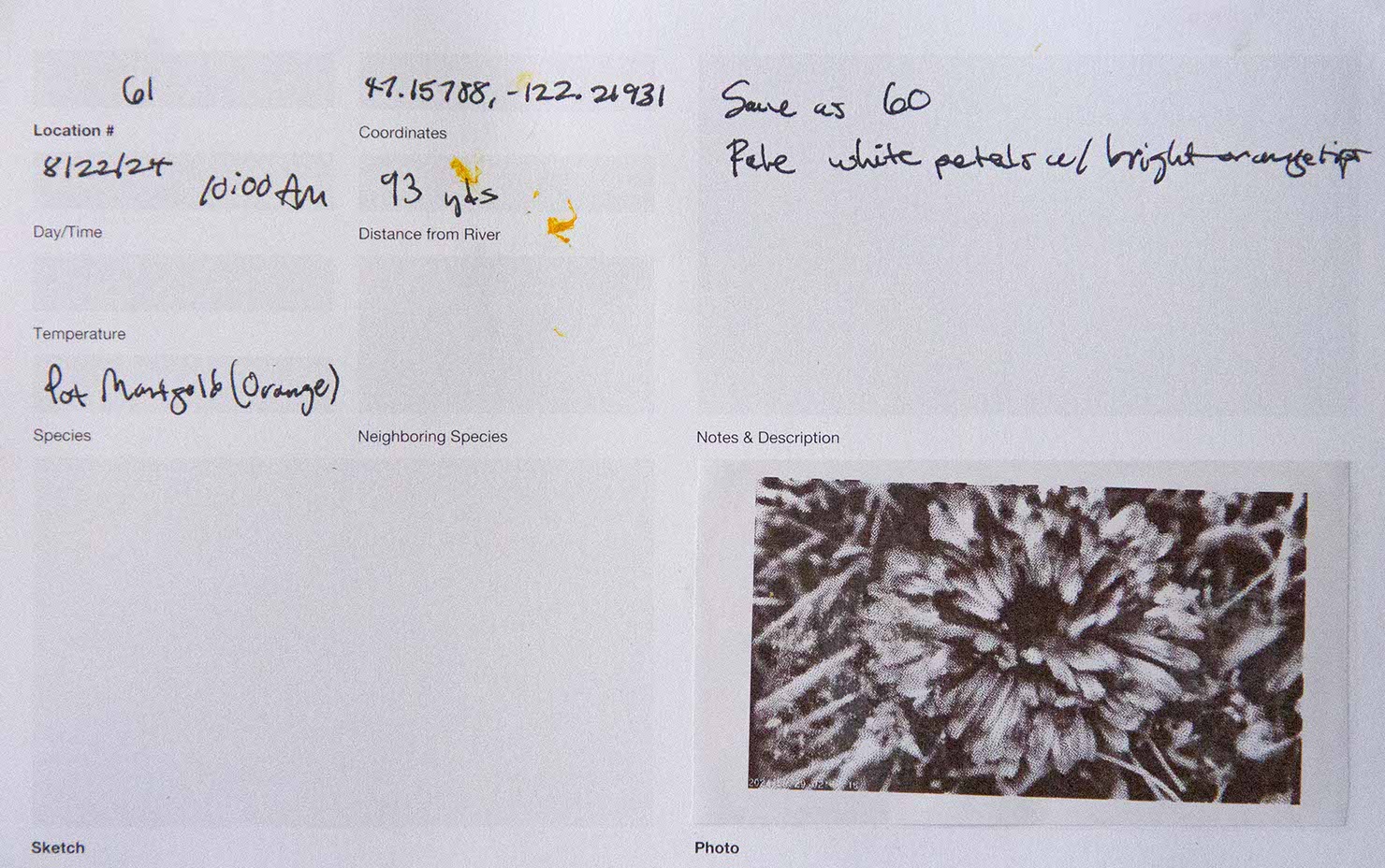

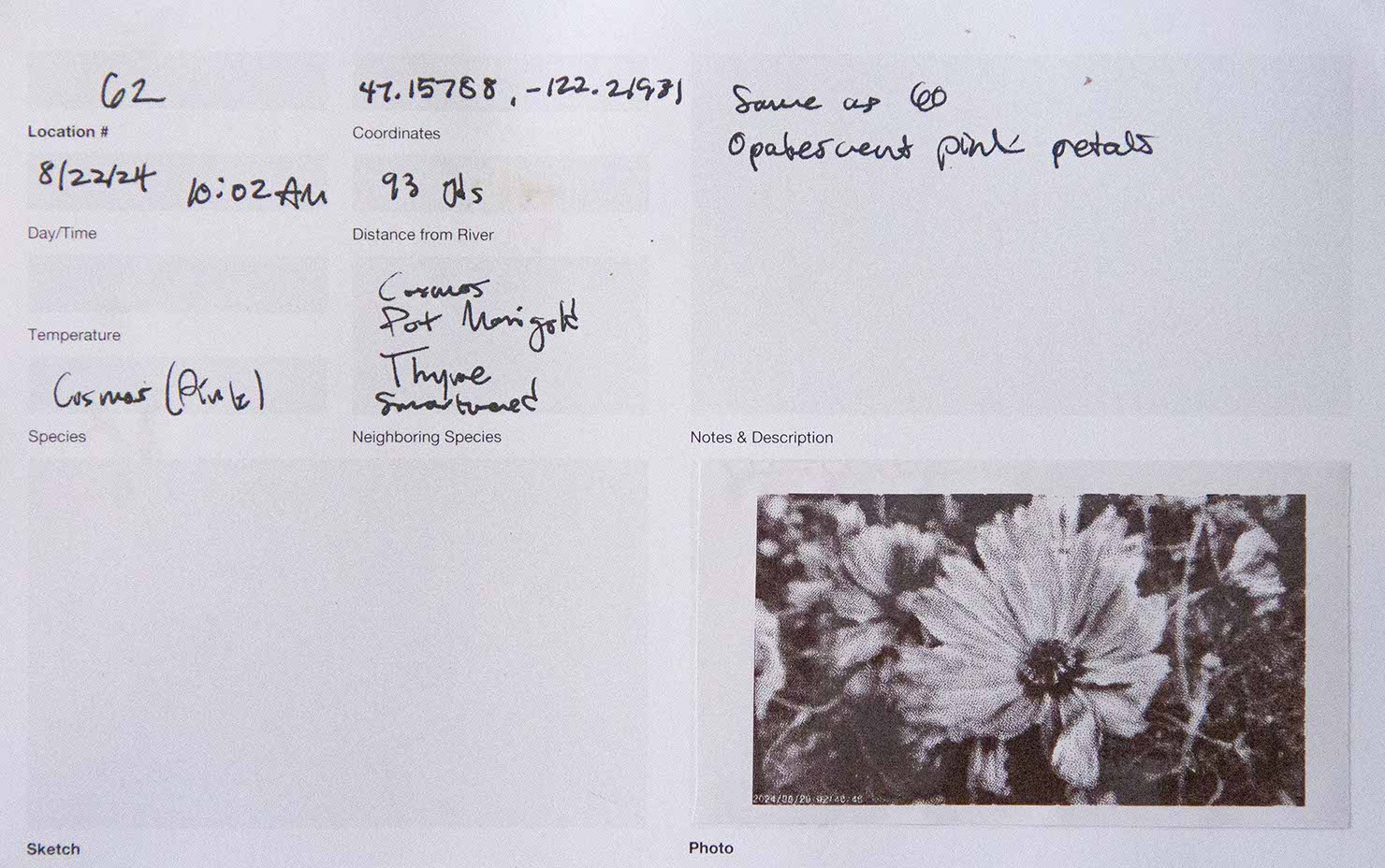

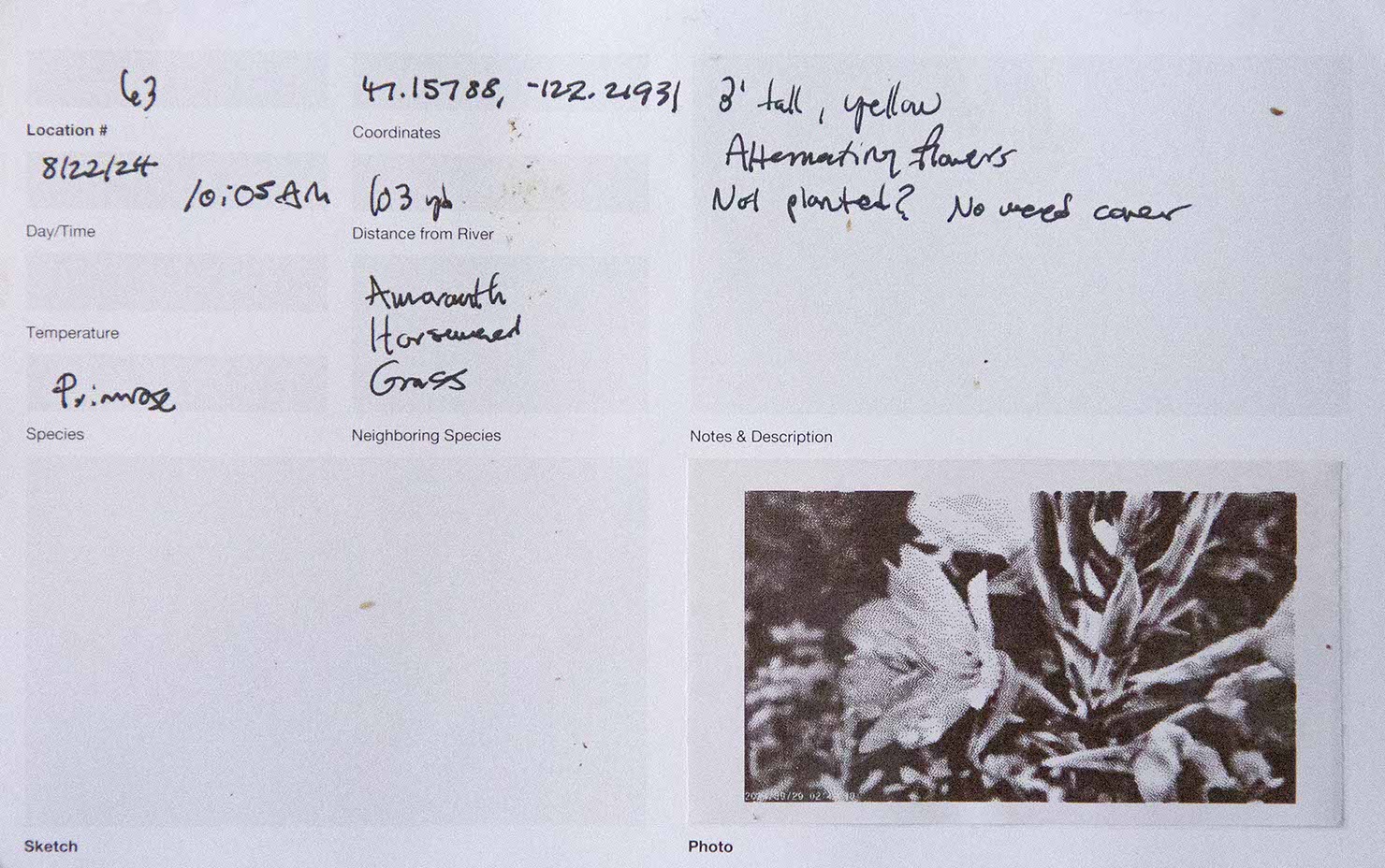

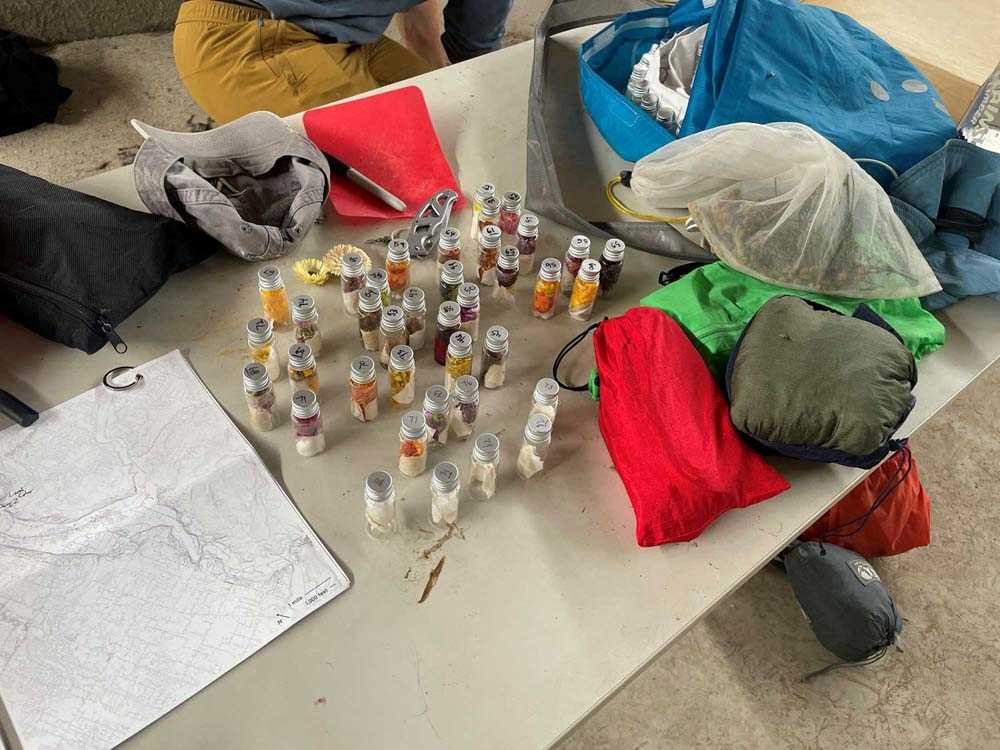

We pre-mordanted fabric in order to dye passively along the route. We prepared four different treatments of fabric, cut each into ¾” squares and pre-loaded them into numbered vials.

Each vial corresponded to one location at which we collected materials to dye with. We aimed to collect 2 samples every 15 minutes.

We pounded or crushed a sample of the material to test if it might give color.

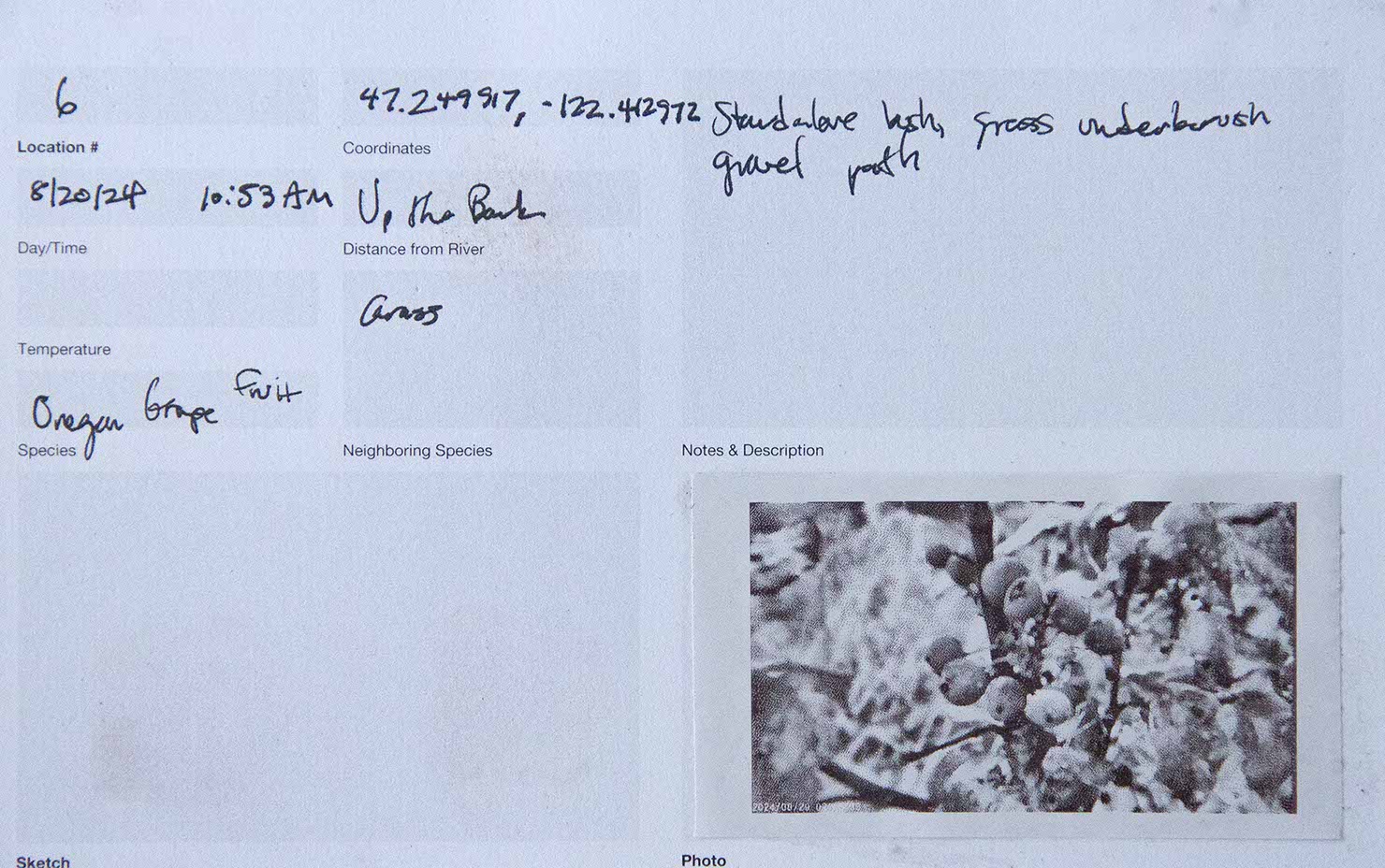

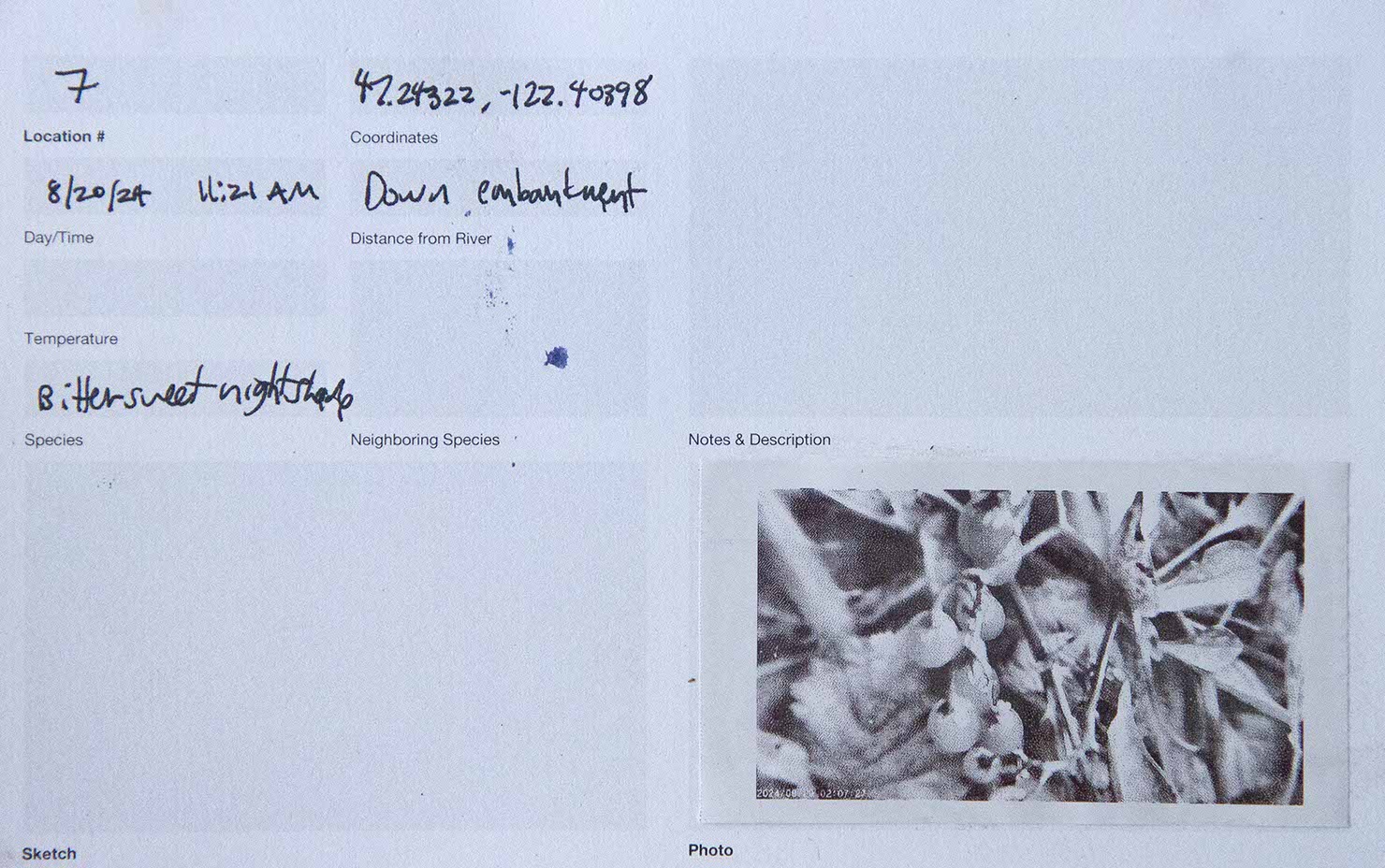

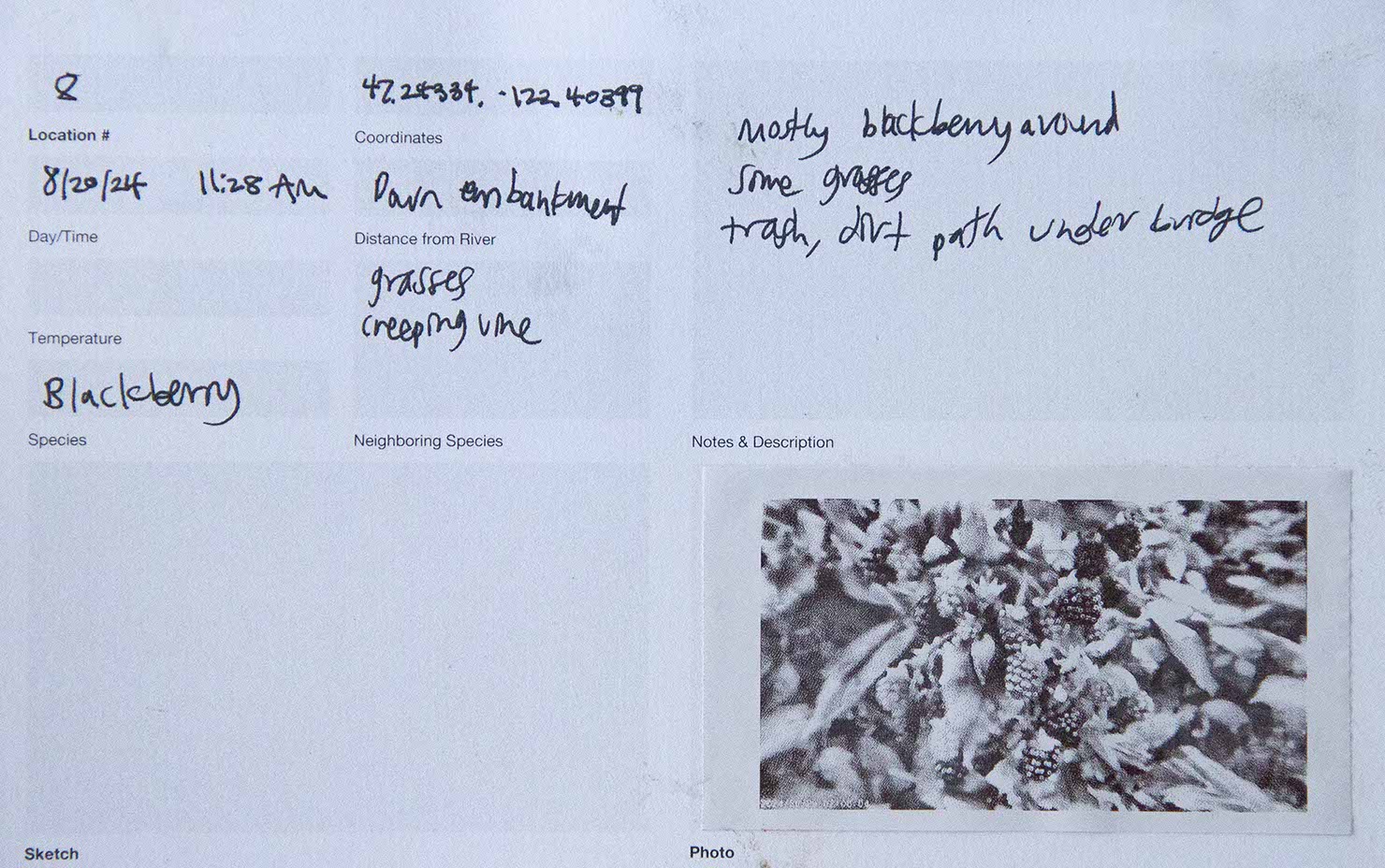

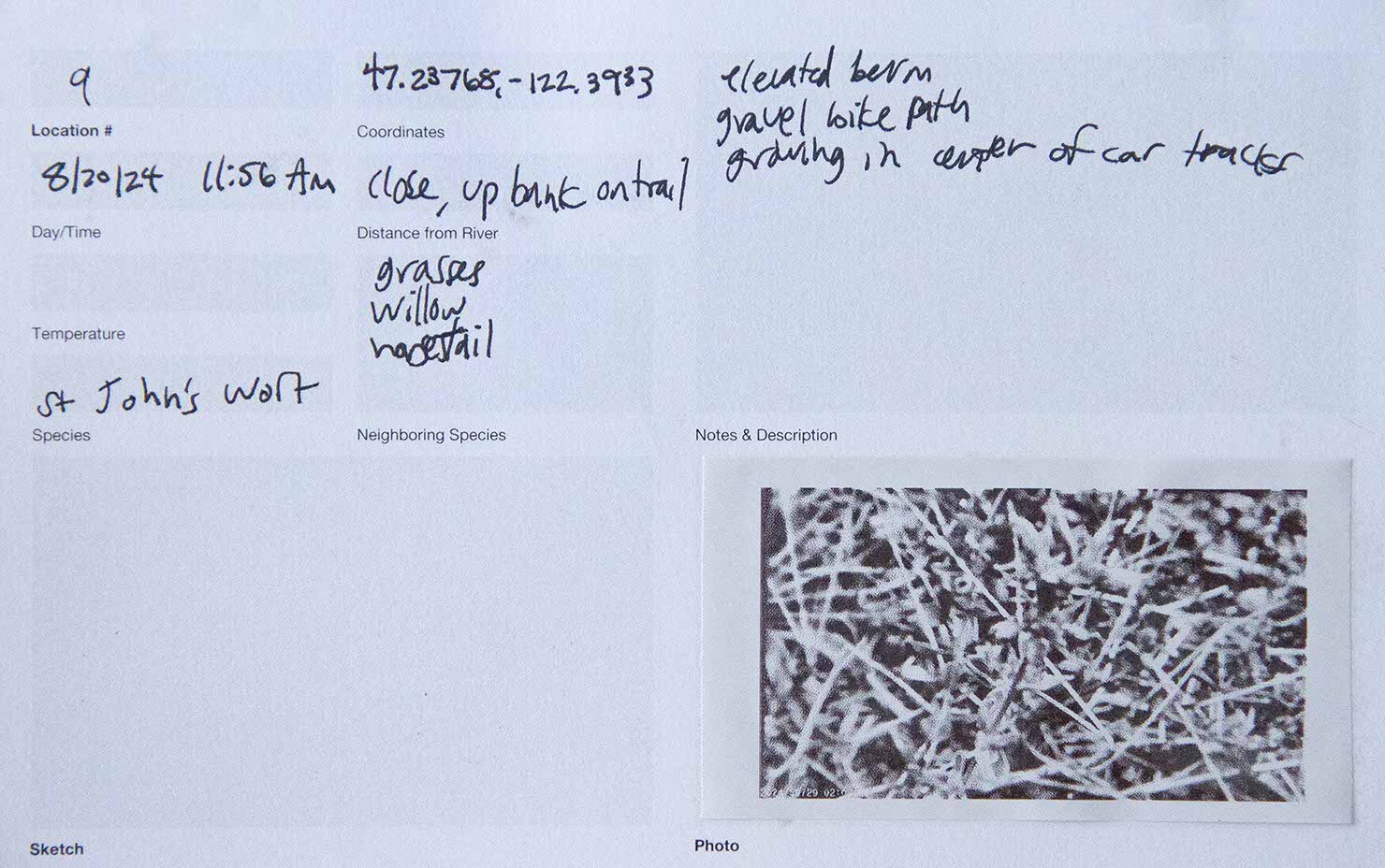

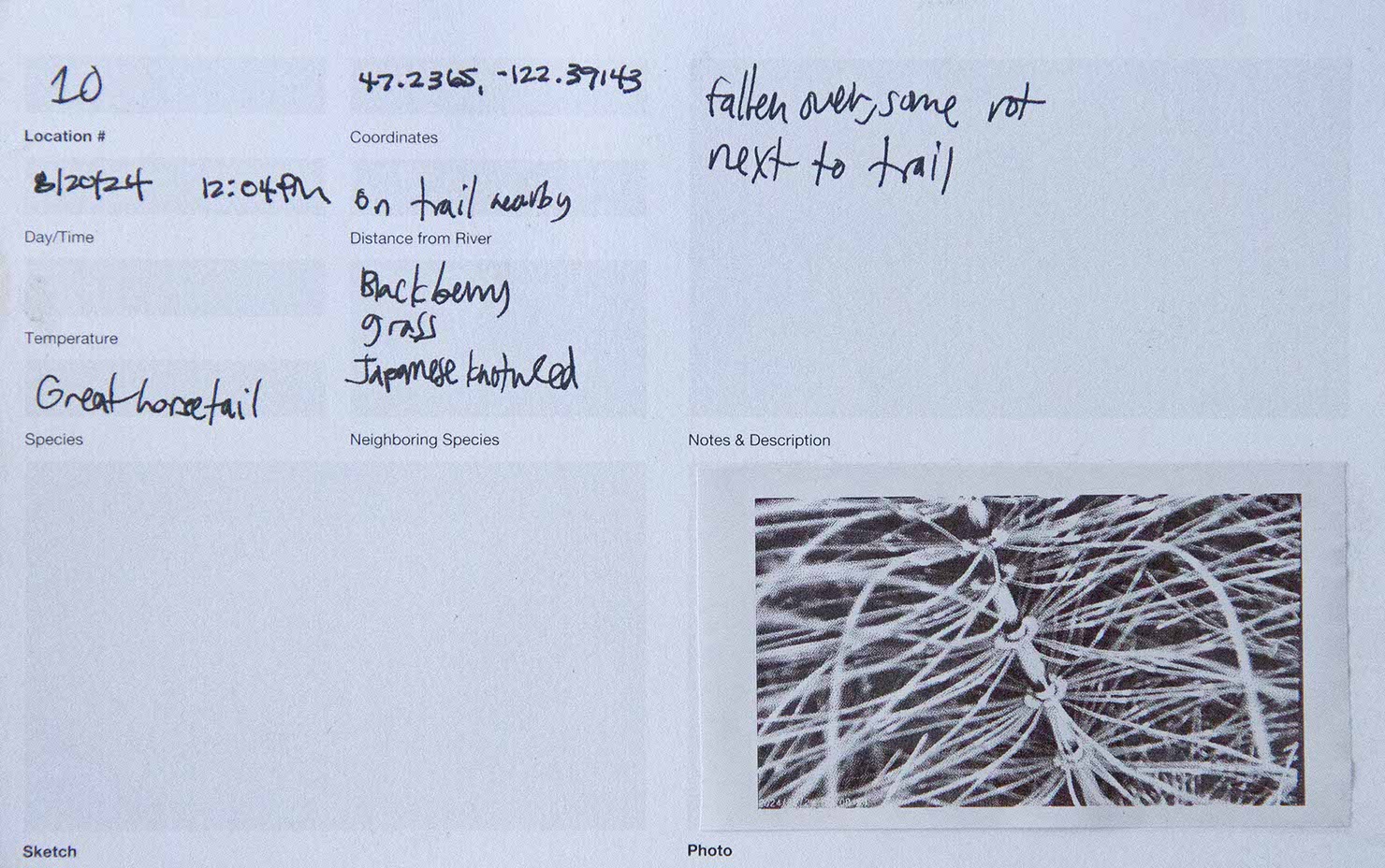

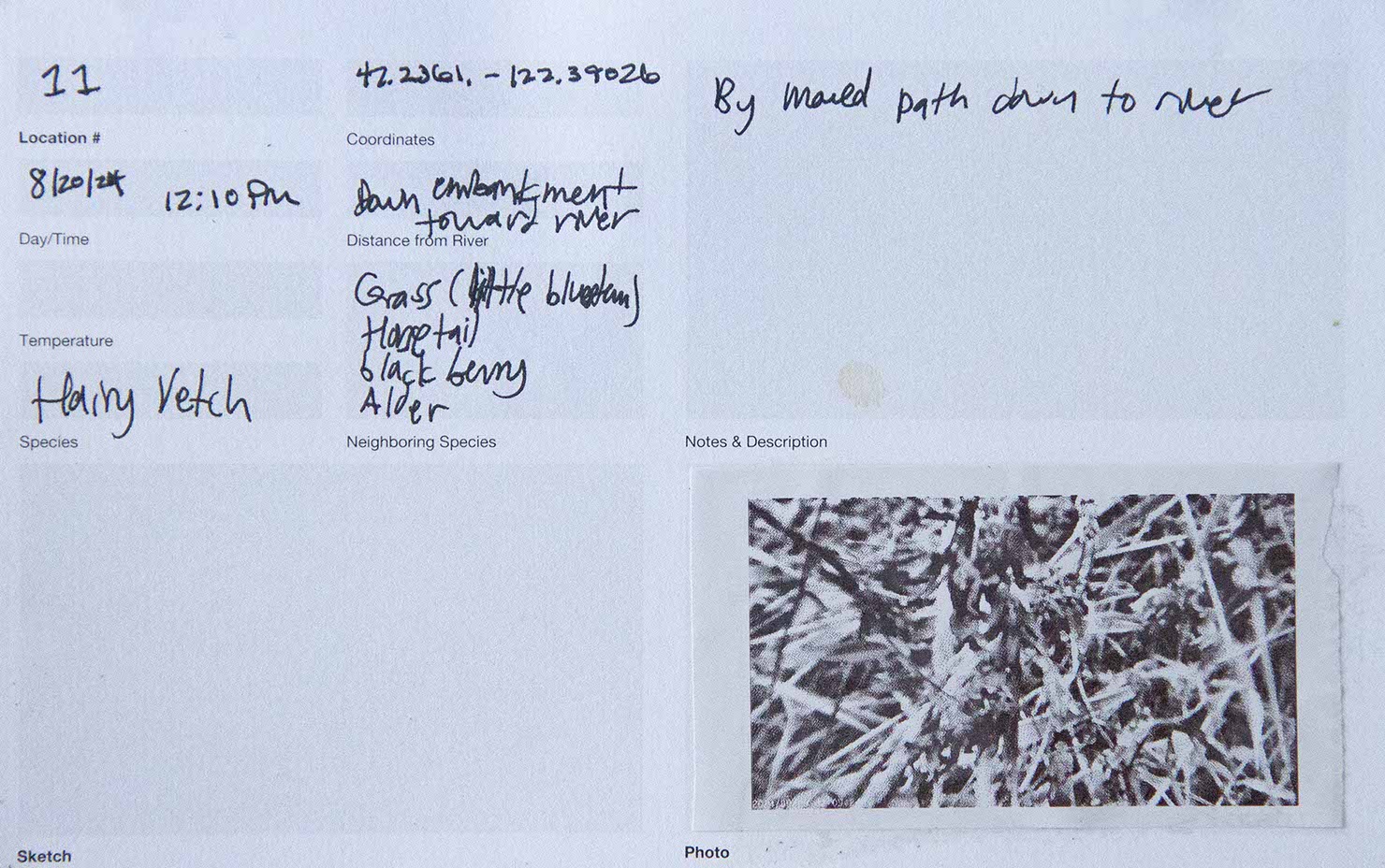

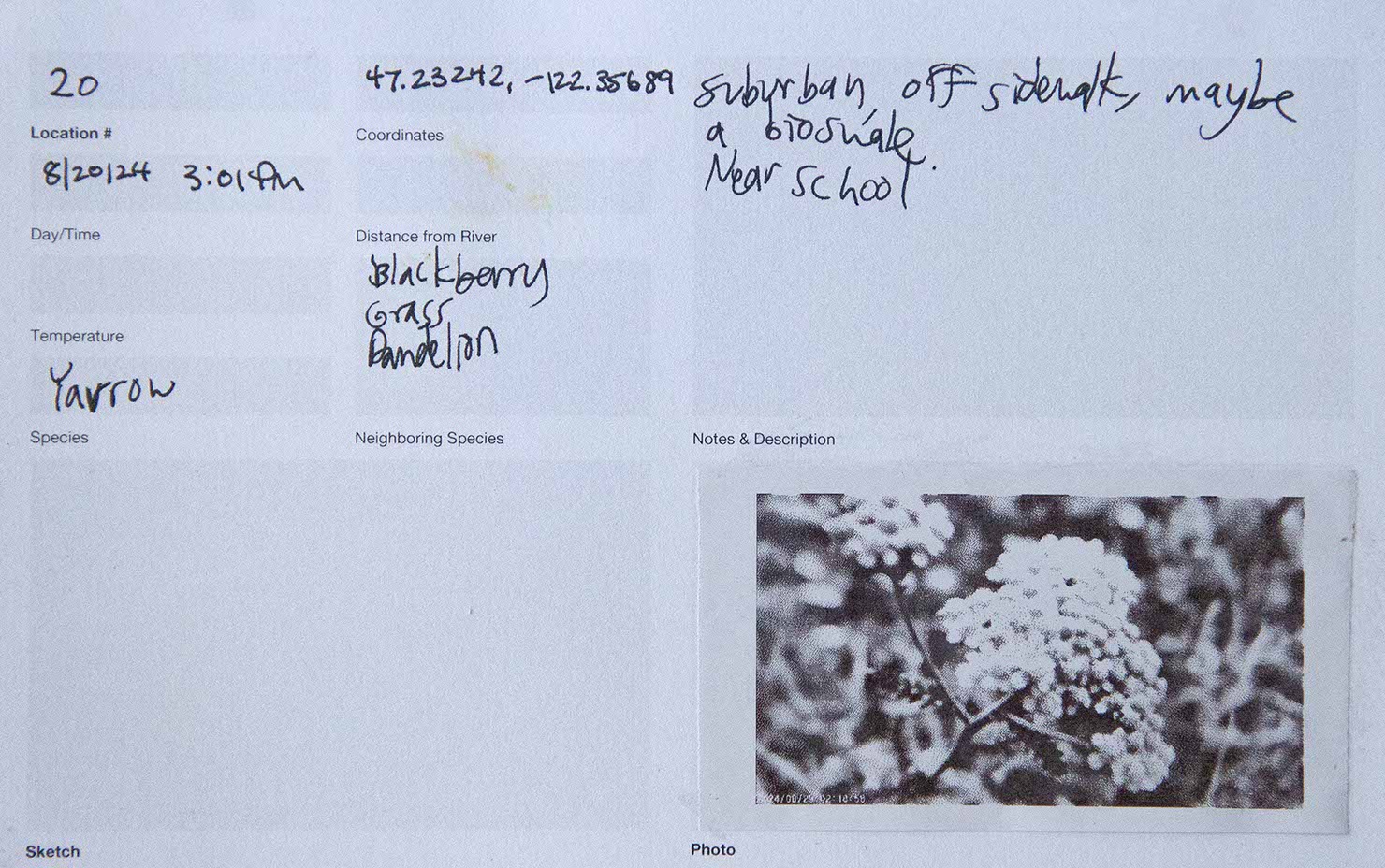

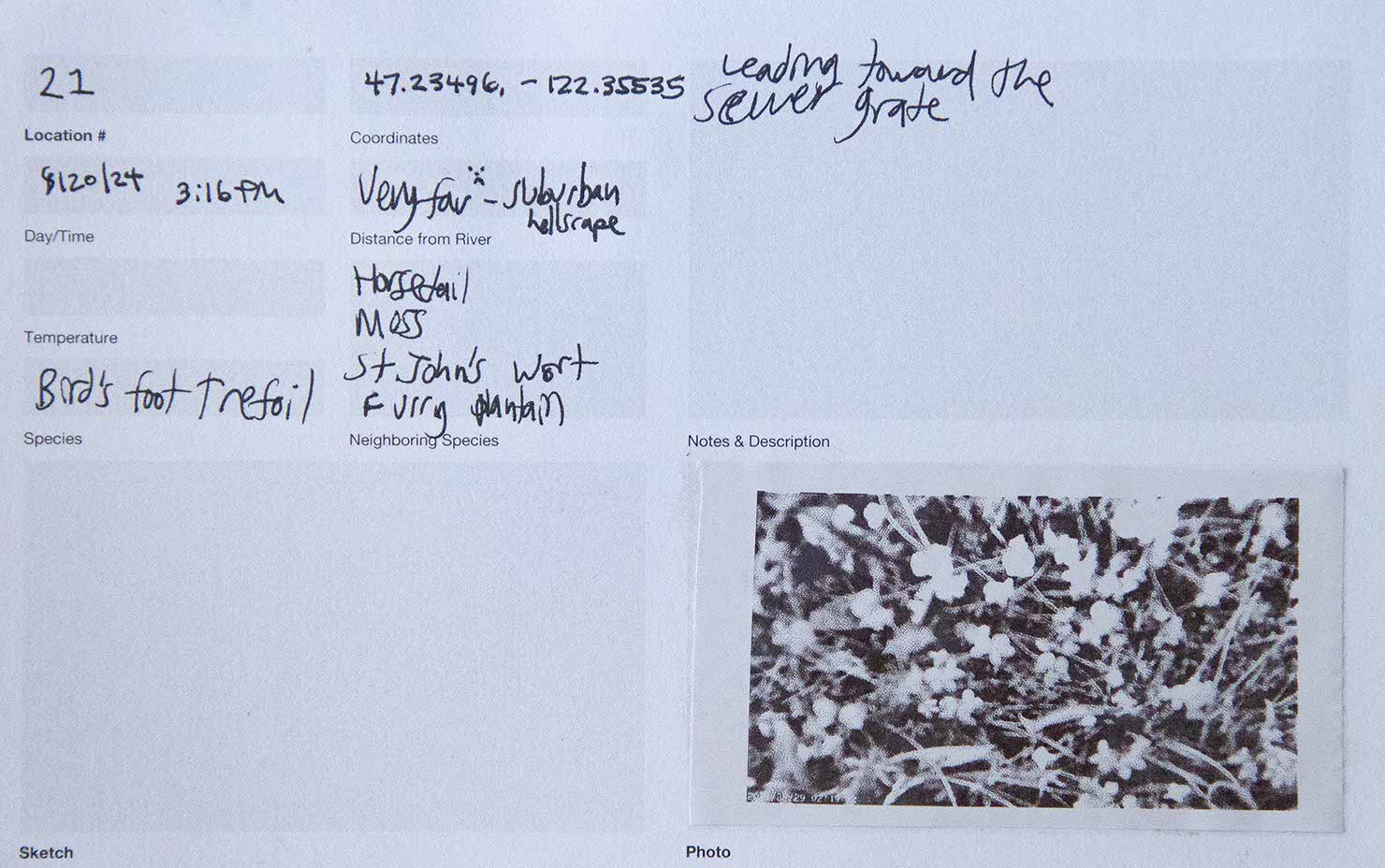

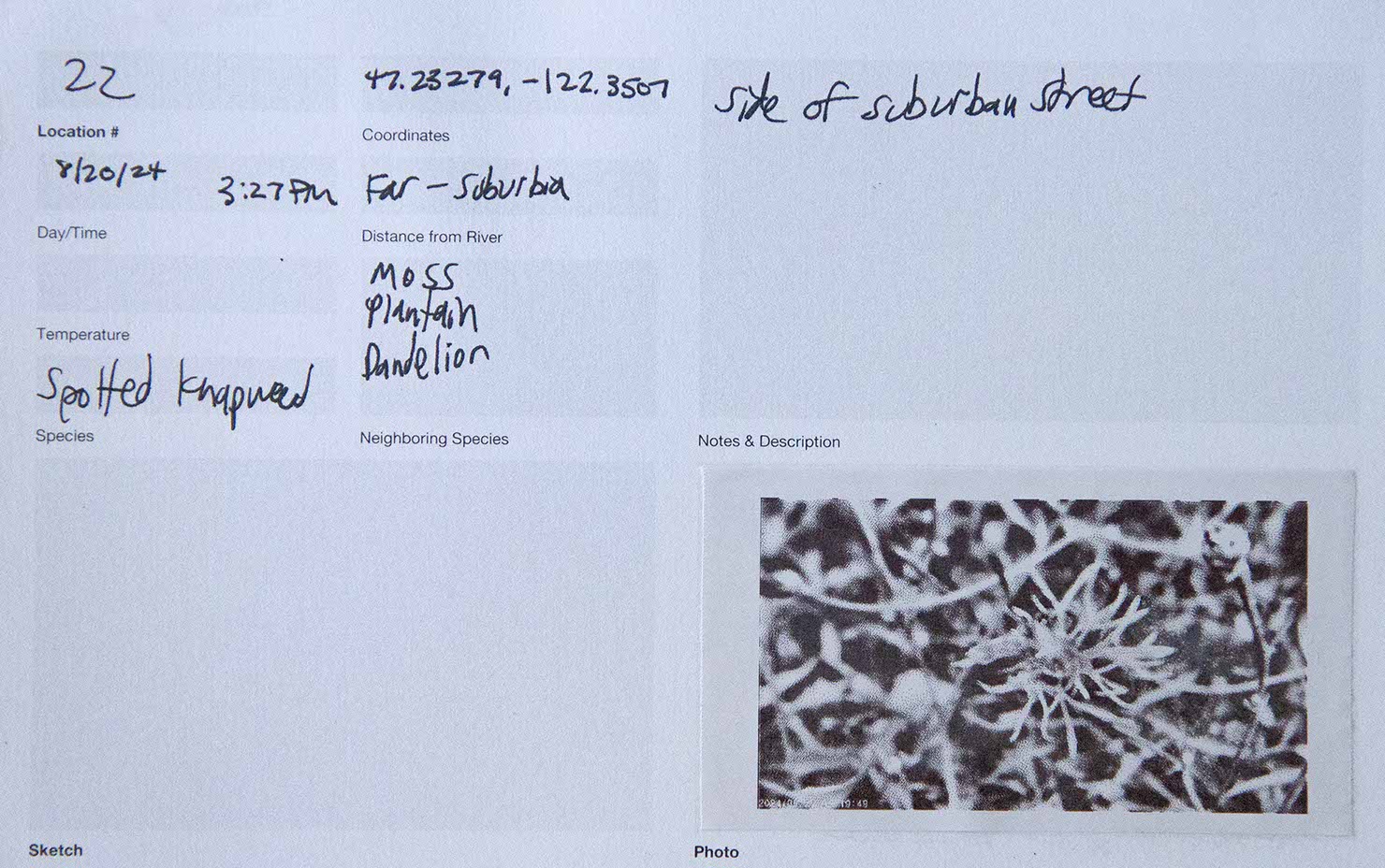

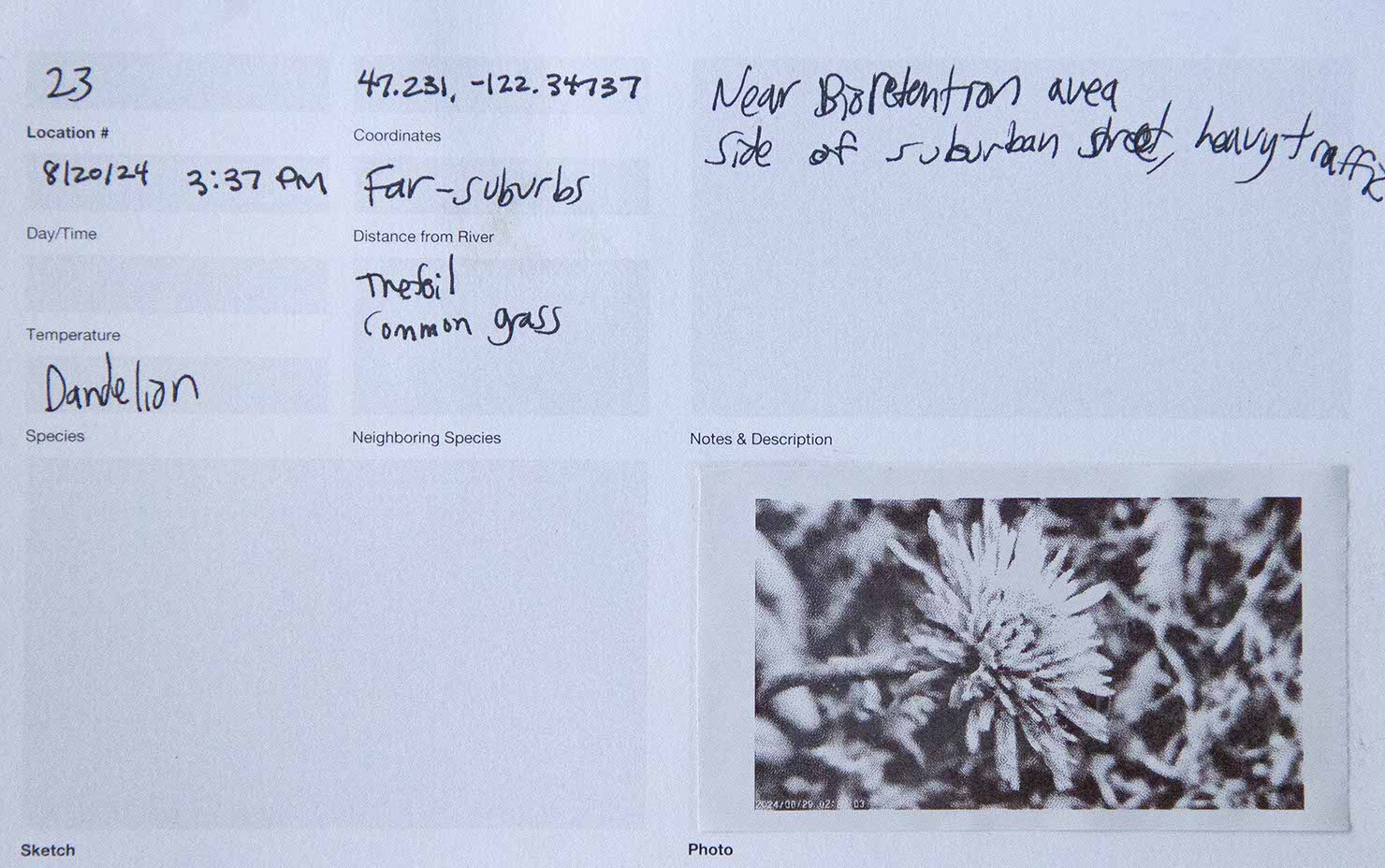

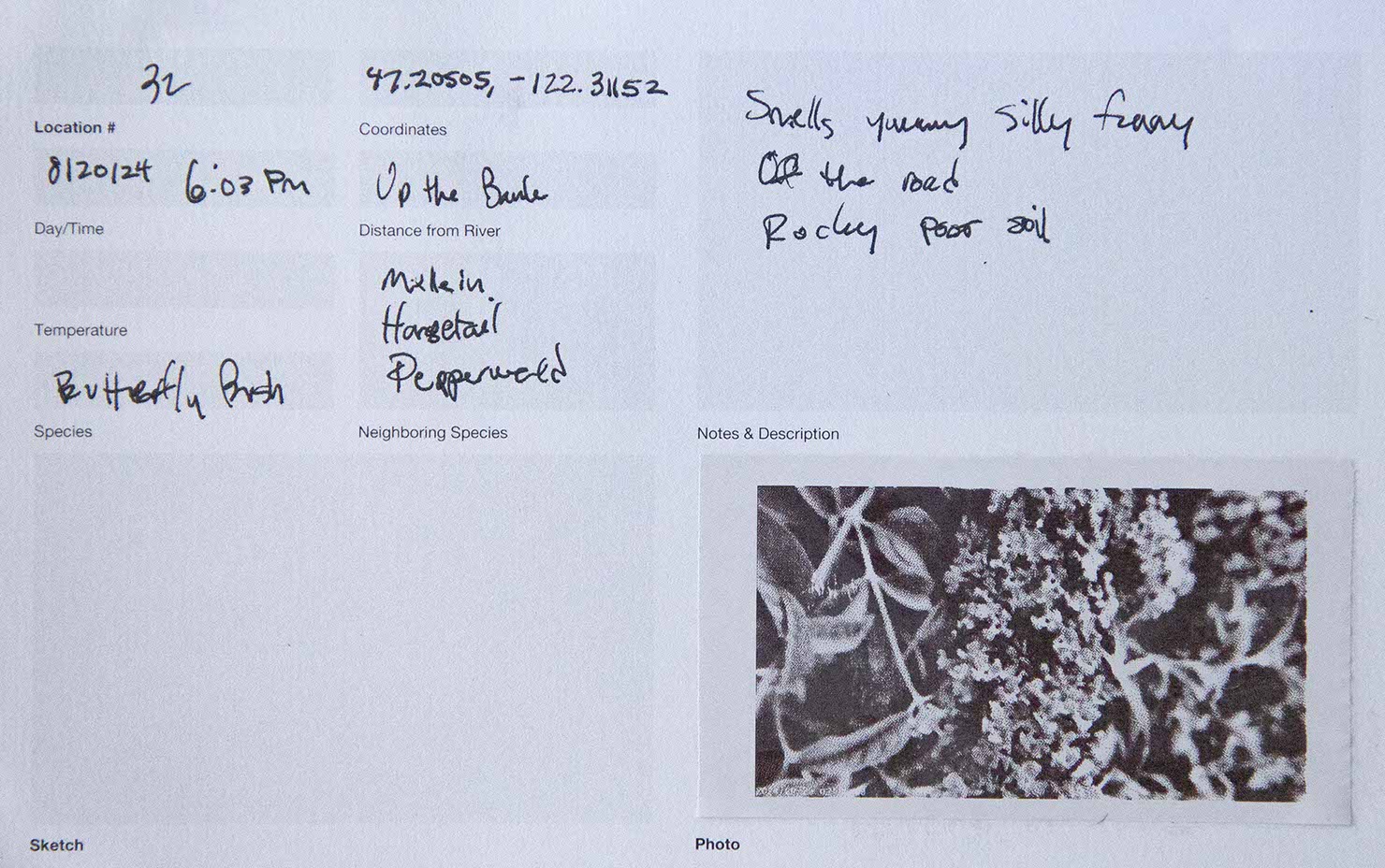

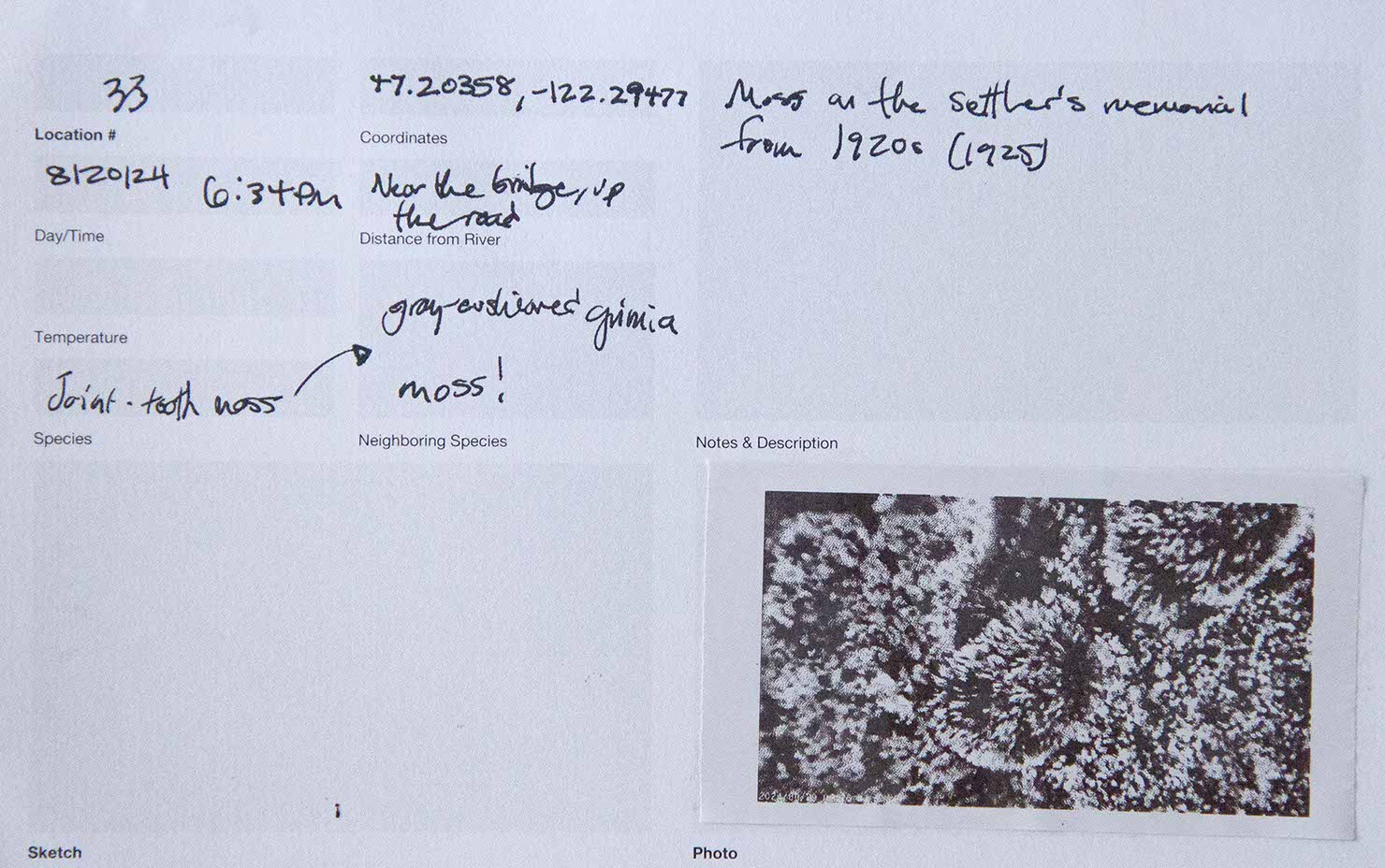

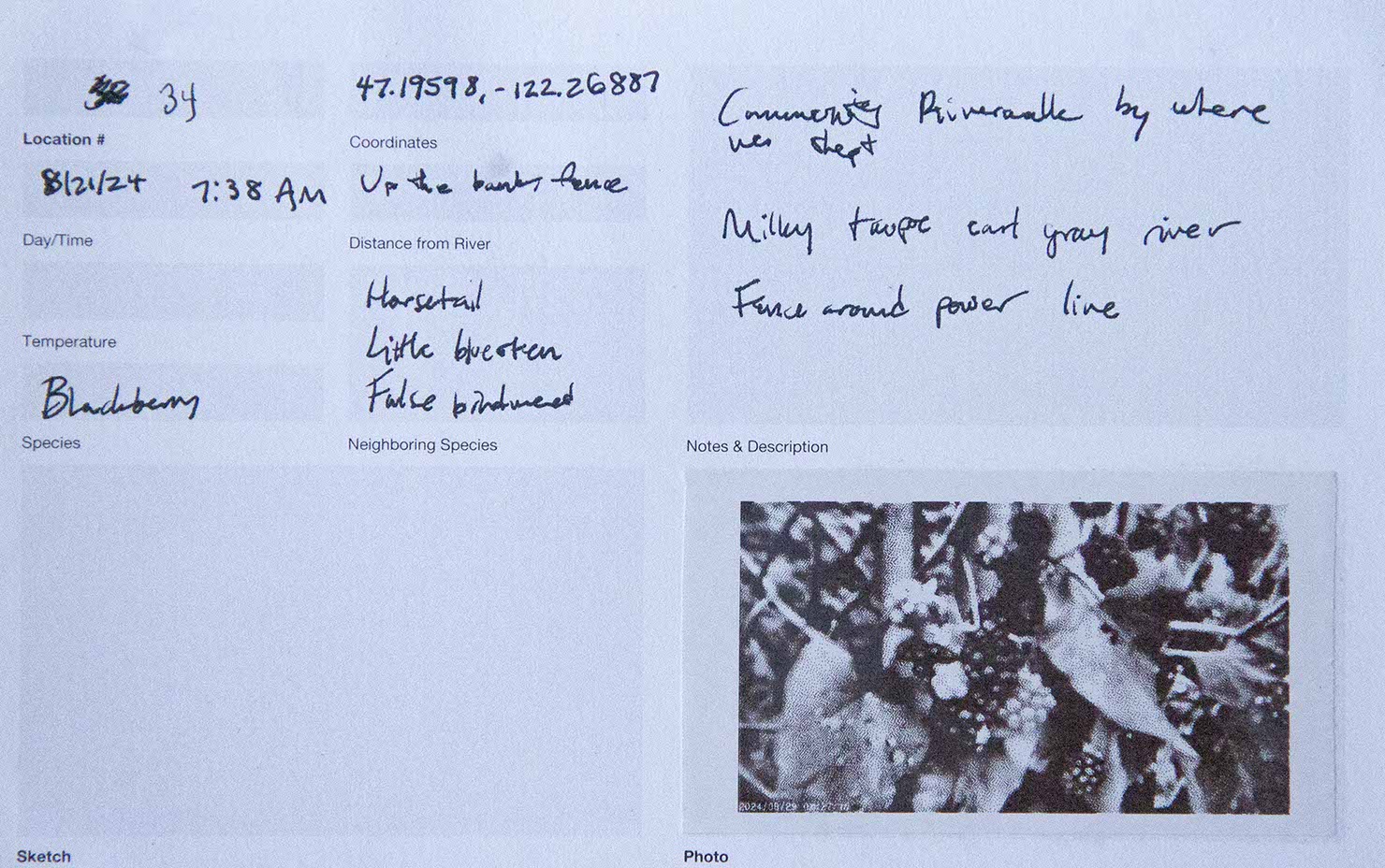

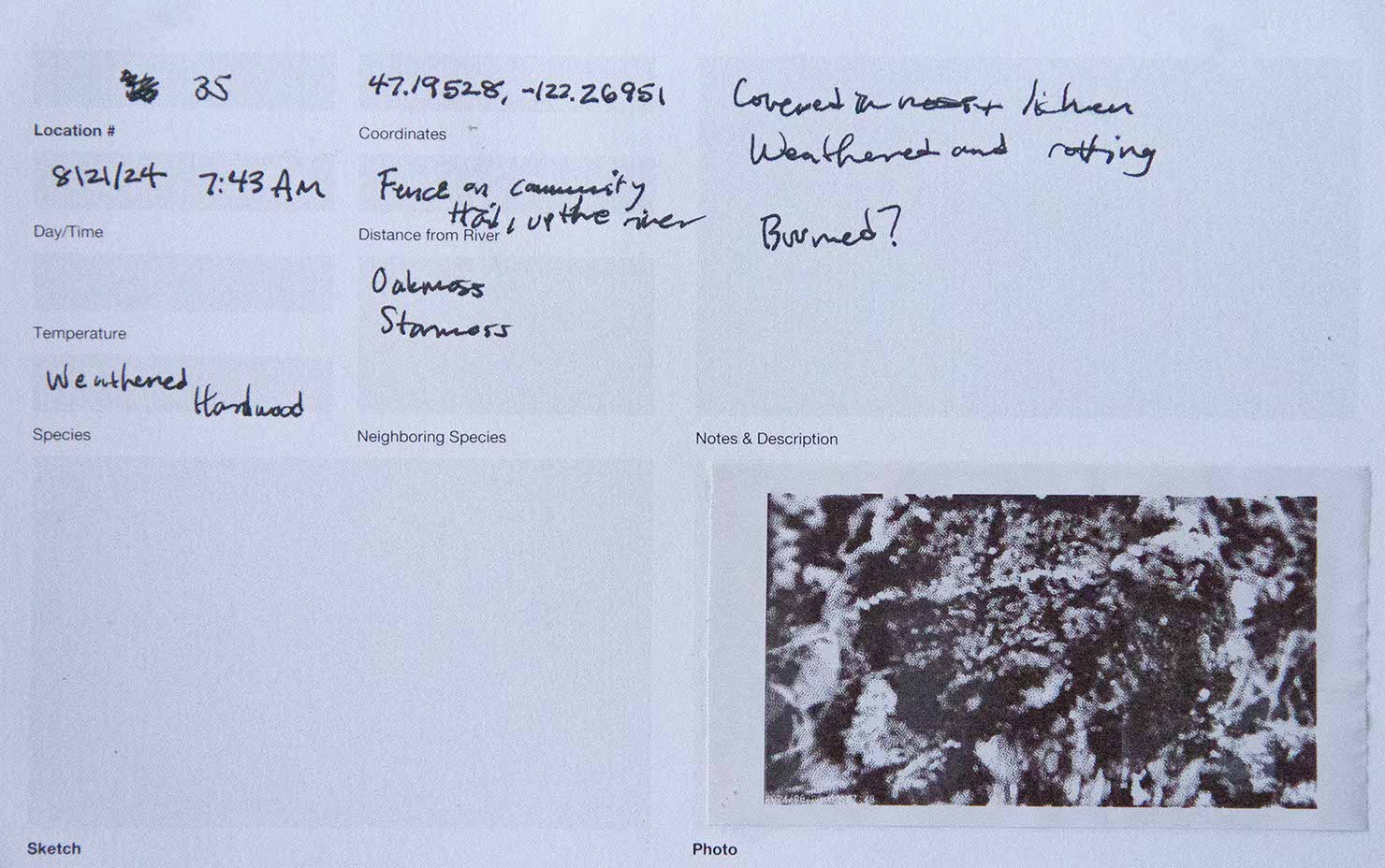

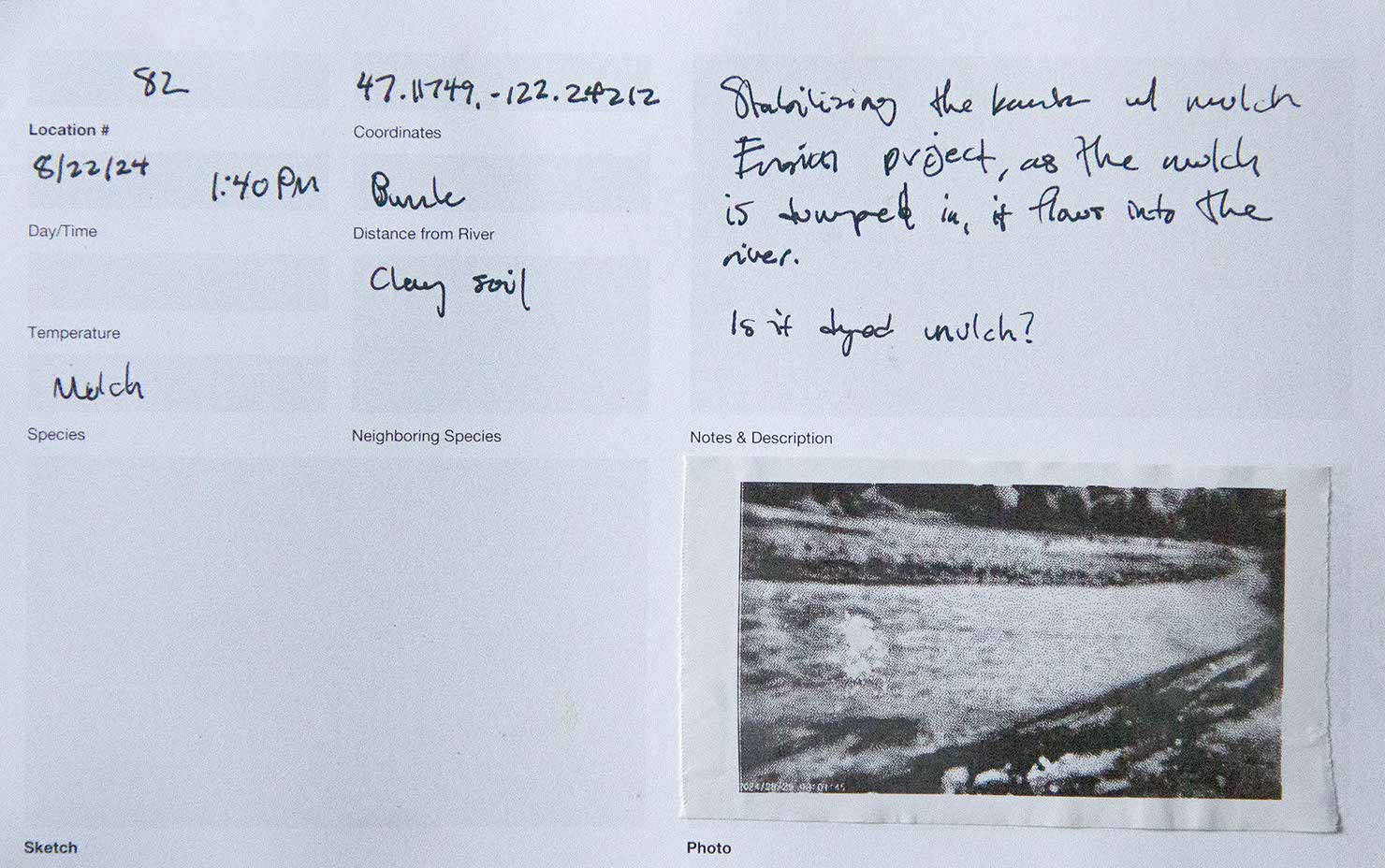

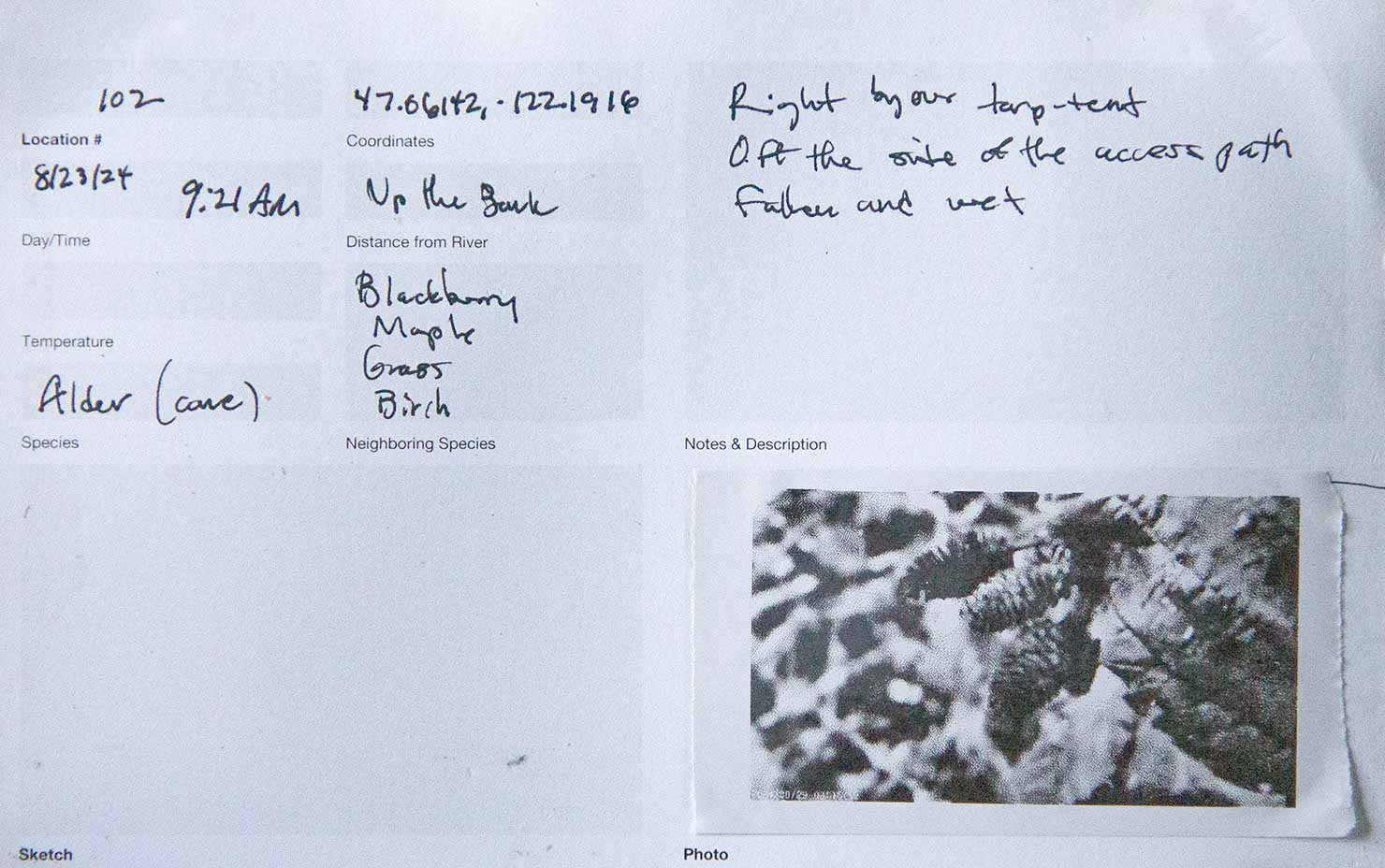

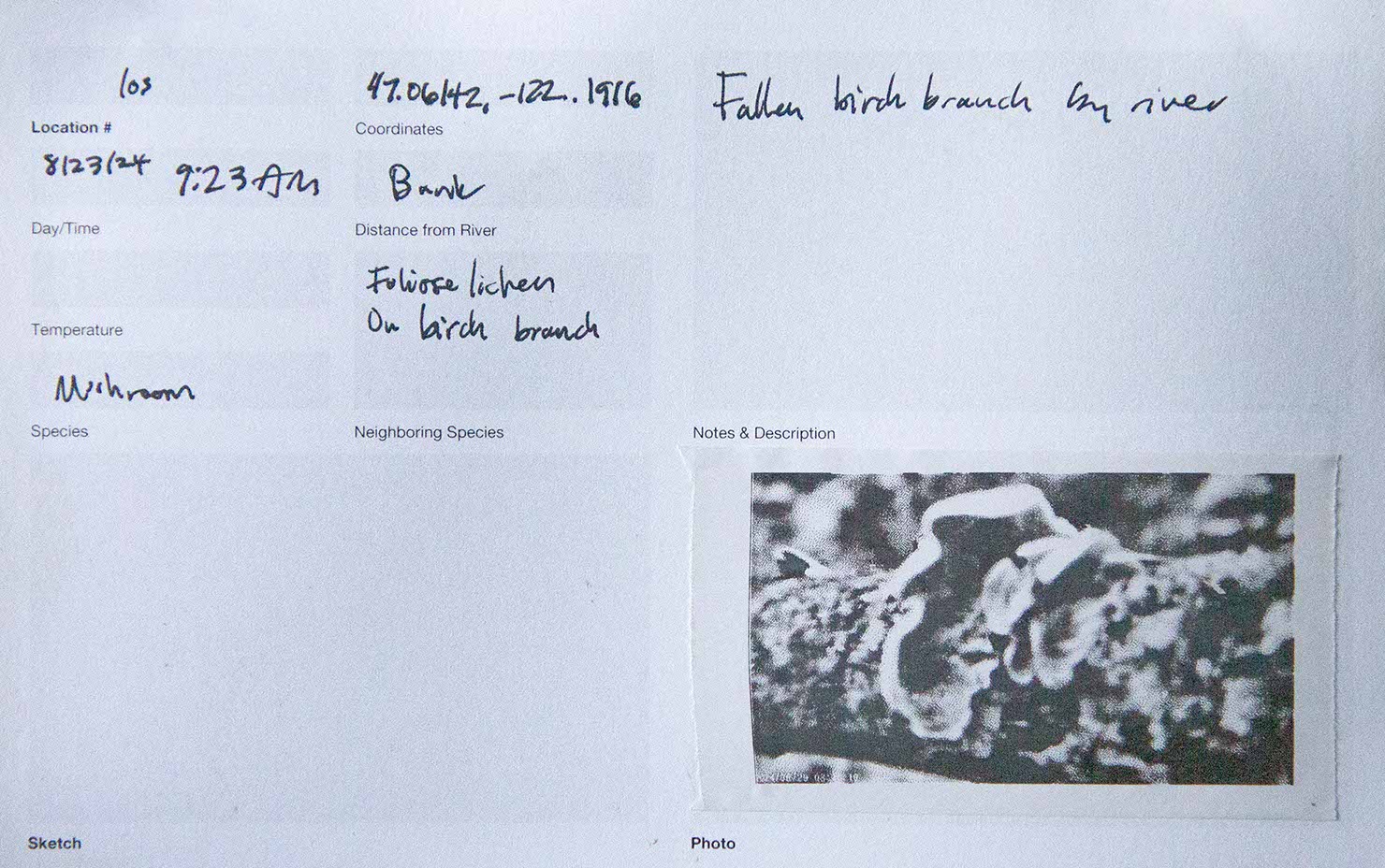

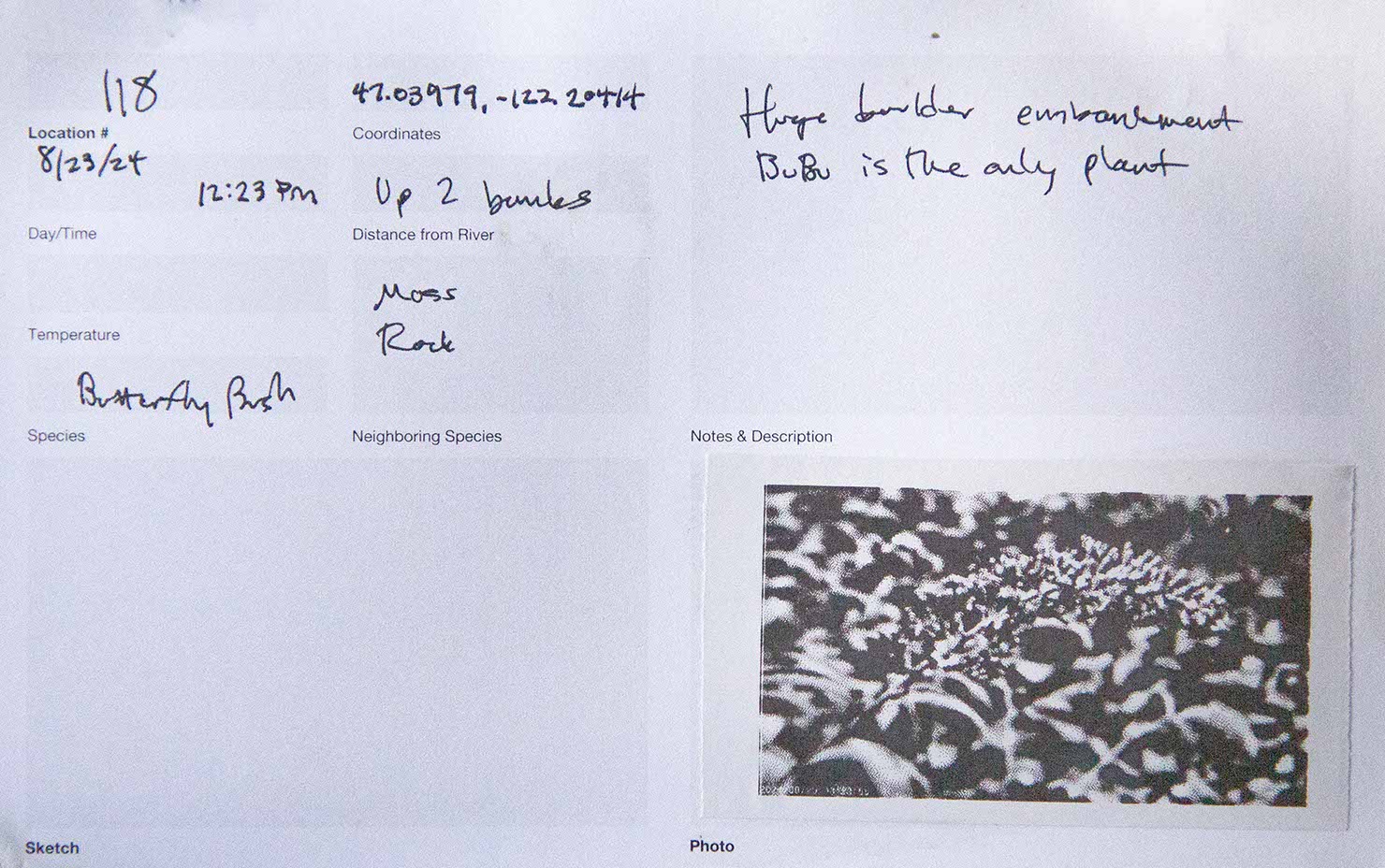

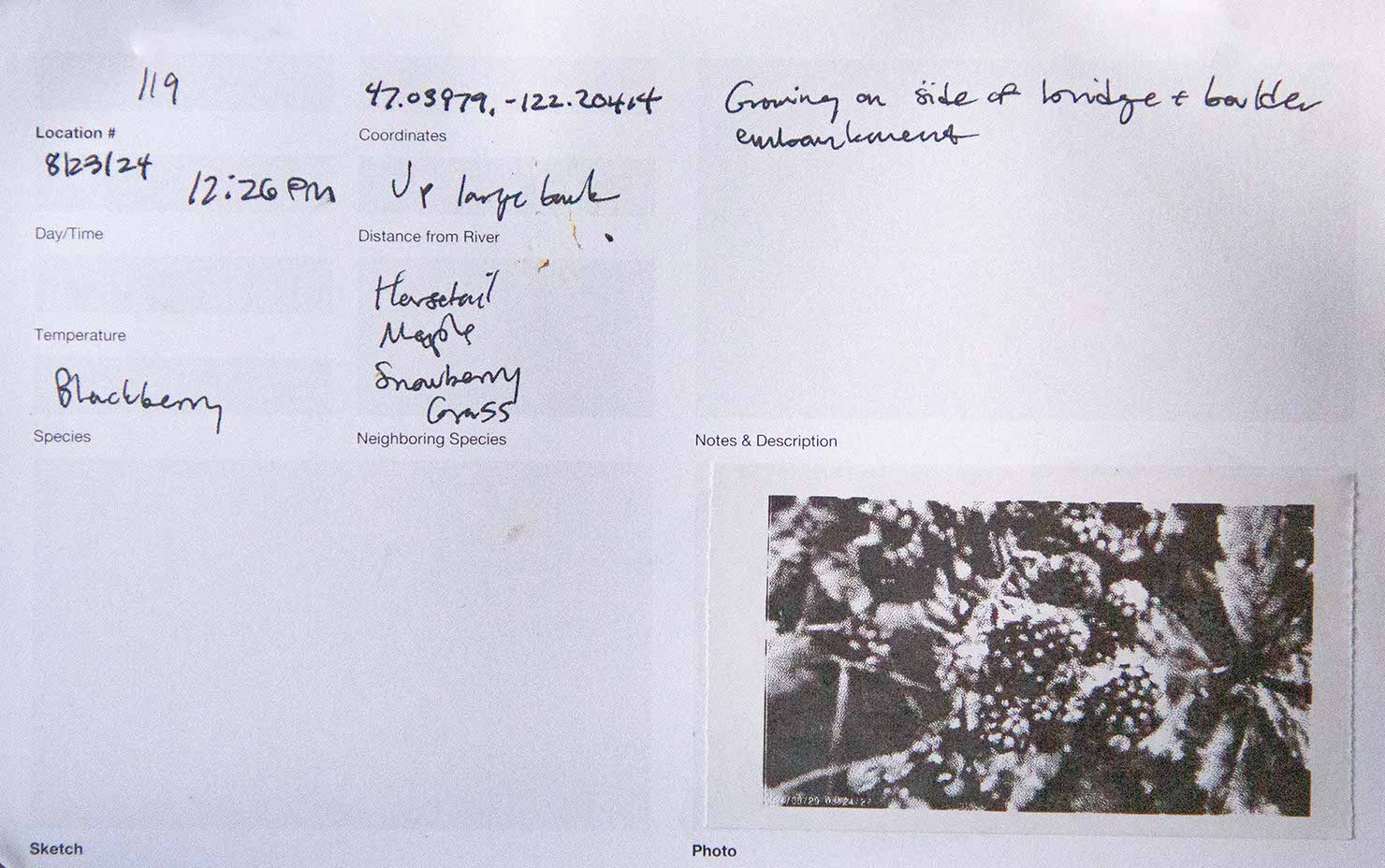

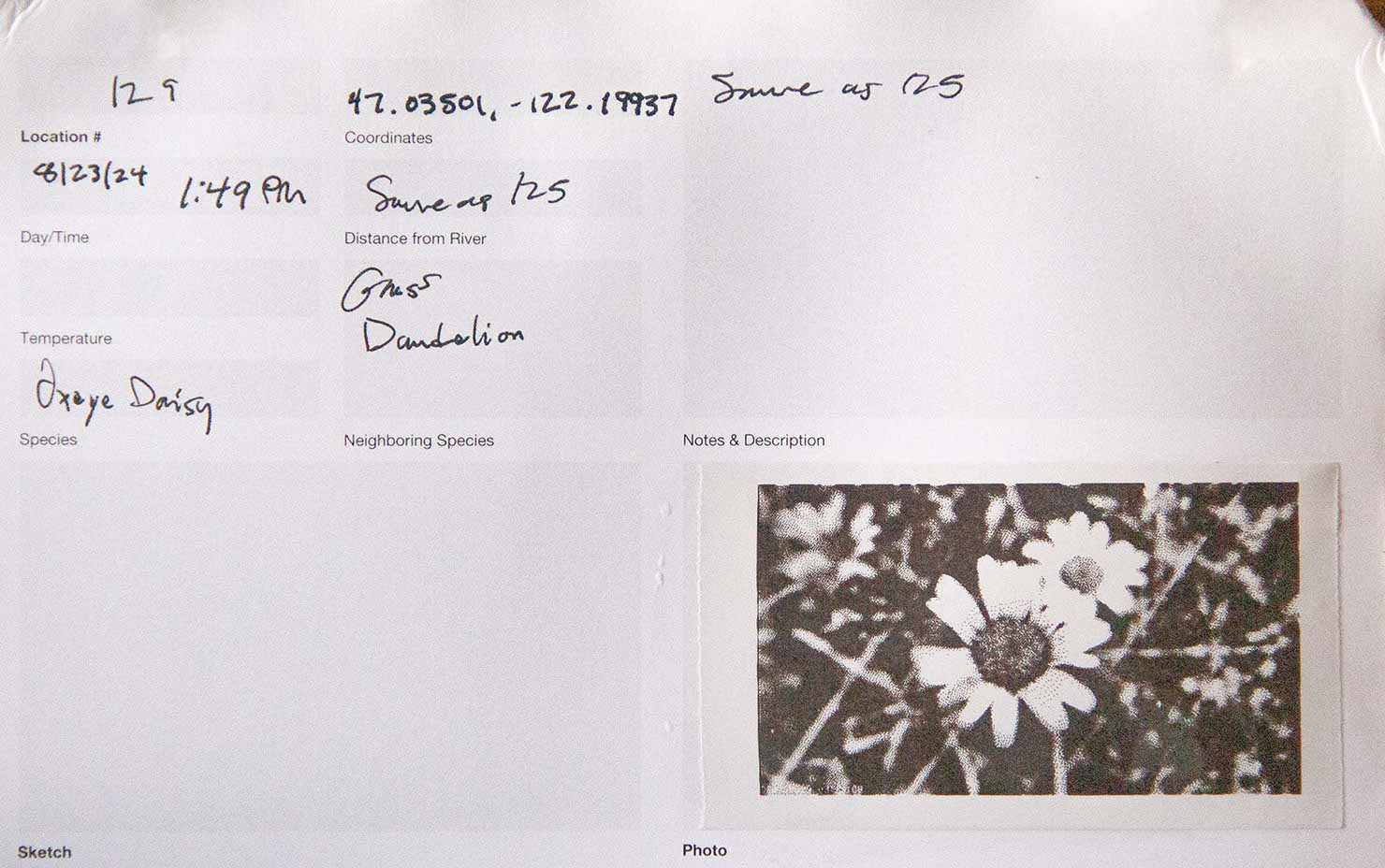

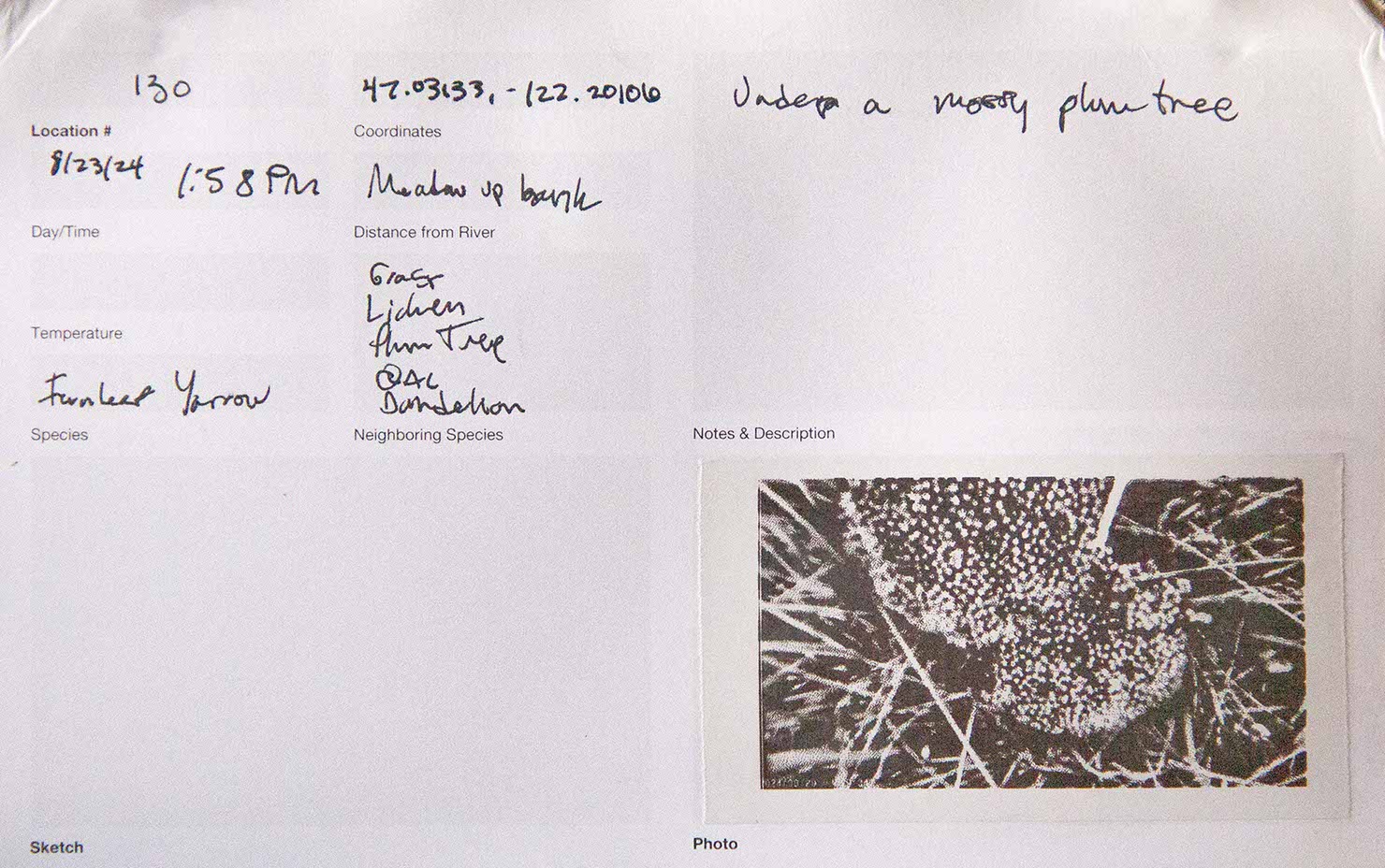

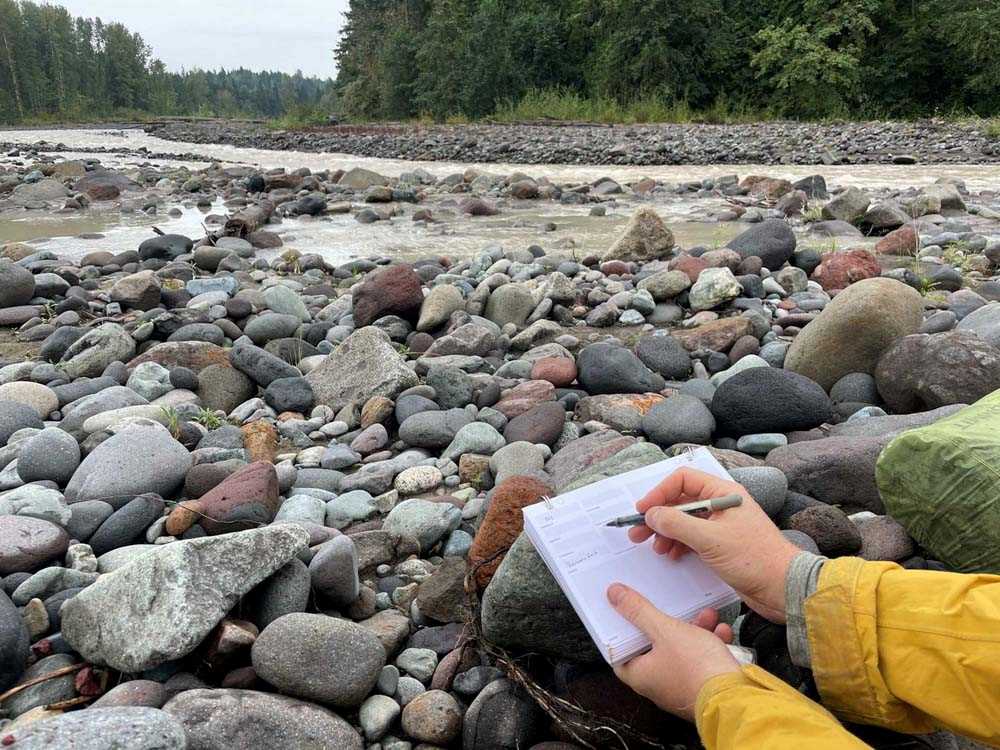

We recorded the location code, coordinates, distance from the river, time, date, and other observations in a field book.

After we collected a sample, we placed the vial in numerical order along a wearable and stashable wrap. This 20-foot-long wearable tool organized and made visible the results of our process. Its linear form mirrored our one-way path along the Puyallup River.

The next morning we collected one bottle of river water, boiled it and poured it into the previous day’s vials.

Along the ~45 mile course of our walk, we felt the river gradually transform

from a heavily-abused conduit (for water, trucks, electricity, trains,

shipping containers, and industrial chemicals) built atop wetlands

to a fast-flowing fishing and urban recreation

grounds that bisects the Puyallup reservation

to a privatized resource nourishing

agriculture with water and alluvial sediment

to an active site of construction and contemplation

to a sometimes-accessible leisure place for the parcelized exurbs

to a sparse corridor for rural electrification,

lumber mills, stream depth gauge stations

to a rocky bed sitting beneath steep coniferous forests

to a wide and braided ecosystem where deer and birds subsist at the

margins between the lowlands, the quarries, and the clear-cut forests.

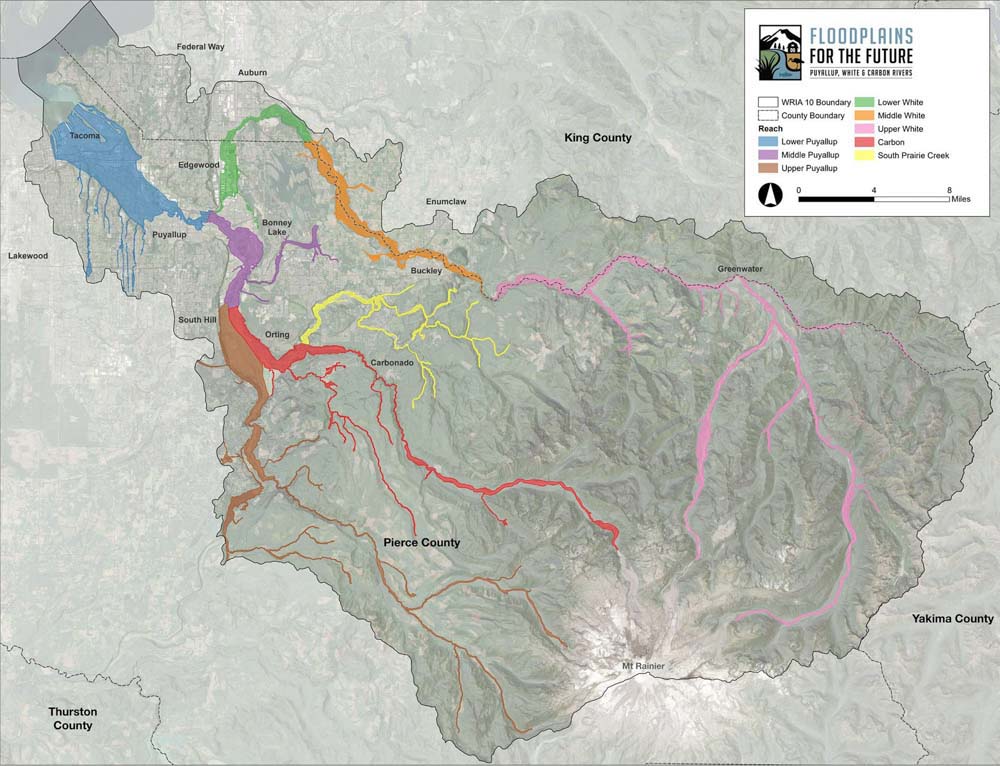

Ecotone proposes the term colorshed as an intervention. Like other “-sheds” such as watershed/viewshed/airshed, colorshed describes a physical region within which one can locate themself. Watershed, for example, deterministically describes an area within which every drop of water flows to one shared water body. A typical watershed map shows a closed geometry, segmenting an otherwise continuous landscape. It is a term often invoked to permit the construction/continuity of extractive water infrastructures or to mobilize a neoliberal imaginary of land stewardship.

Courtesy of Floodplain for the Future

Colorshed, we propose, describes a place or region’s color palette. Every place-moment within a colorshed has physical colors that exist elsewhere in that colorshed. It is the pigments found in plants, the color of rocks, the shades of building materials and billboards, the hues of feathers. A colorshed is not only geologically determined, but constantly remade by people, plants, animals, abiotic factors, the built environment and the relationships between all these things.

Creating maps and other visual representations of an imagined Puyallup River colorshed from found pigments helped to heighten the subjectivity of cartography by recording ephemeral and hyperlocal data. It is only through the prisms of seasonality, histories of the land, animal and vegetal agency, pure happenstance, and one’s own positionality that abstracting and visualizing elements of this landscape became possible.

Thus, the project used “colorshed” as a conceptual tool, among physical tools, to guide our decision-making before, during, and after the act of walking along the Puyallup River. Colorshed is both a way to imagine a place and to represent that imagination.

We tinkered with old tools and produced new ones to structure a relationship with the Puyallup River. If a tool is simultaneously an extension of the body, an implement that performs a specific function, and a vessel for ideology, then one can relate to place in a hyperlocal and subjective way through fashioning one’s own tools.

This project would not have been possible without the support of Emily Tzeng and Brian Love from Local Color Fiber Studio. Sara Gotowka, Julie Beeler, Kayla Powers, and Francesca Benedetto offered indispensable guidance on conceptual, logistical, and ethical questions. We are grateful to the many scholars and artists whose ideas have also indirectly produced this project–Garnett Cadogan, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Anthony Acciavatti, Pierre Belanger.

The Puyallup tribe has stewarded the lands we walked since time immemorial. We are indebted to their care for the waters and beings of these lands–past, present, and future. It is because of Puyallup resistance, specifically to industrial pollution of the rivers and streams, that we can still walk along a dynamic and living river.

Finally, we acknowledge the Penny White Project Fund for the opportunity to conduct this research. This work is part of a collection of projects that carry forward Penny’s ideal of a culture which emphasizes a close relationship between people and nature in a cohesive living environment.

G Laster (they/them) is a researcher and designer whose work seeks to reconfigure material conditions and to fabulate tools toward anti-hegemonic ends. They hold a Master of Landscape Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. They also hold dual bachelor’s degrees in architectural design and Ethnicity, Race & Migration from Yale University.

Nicky Rhodes is a designer and researcher whose work explores connections between craft, carbon, and collaborative practice. Nicky is a Master of Architecture student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He received a bachelor's degree in Growth & Structure of Cities from Haverford College.